The bibliography, "Said Hajji" was dedicated by Abou Bakr Kadiri to the life and activities of Said in the political, cultural and journalistic arenas. The author published in Volume 1, pages 77 and onwards excerpts from Said's memos along with the author's comments as follows:

"Said's elan and imagination was very fertile; he contributed to a wide range of social issues. While he was developing a project near and dear to him, he never lost sight of its cultural implications. Culture and upbringing were topics of much interest to him. Political issues spurred him to comment on the news as it unfolded so as to avoid being bypassed by the accelerating flow of new events. He also did not want to risk forgetting what happened as time inexorably moved on.

It is for this reason, one would often see him retiring to a secluded spot to write his memos. He would record the events he witnessed, events he contributed to, or simply to construct the broad outline of a future project he wished to accomplish. The records were at times sketchy notes written in haste but meant to remind the author of the events of interest. Regrettably, the memos were not kept in the form of a diary and I was only able to find a few loose fragments of his notes.

But there is no doubt that the contents of these memos provide a truly credible set of documentation about important historical events. The records were personal accounts written during the throws of very heated moments of our history. They are testimonials of key events surrounding the National Movement and its struggle against the colonialist policies of the French people living in our country."

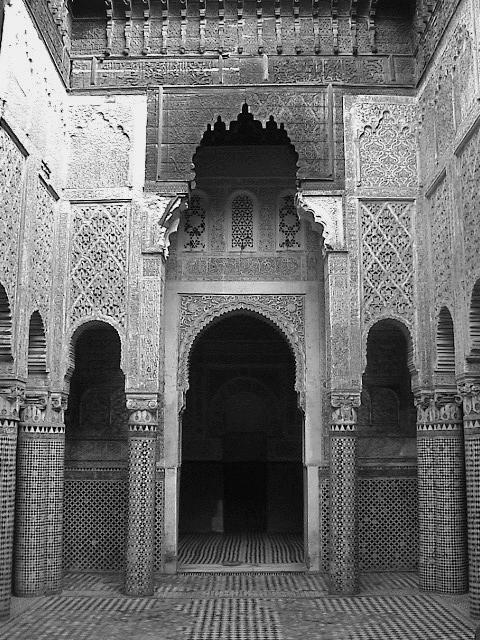

On the right: Main entrance to the Grand Mosque of Salé built during the second half of the twelfth century. Straight ahead: door to the Abou El Hassan Medrassa, a Merinid religious college, named after the Merinid sultan who constructed it in 1333.

Inner courtyard of the Grand Mosque of Salé

The courtyard of the Abou El Hassan Medrassa, named after the Merdinide Sultan who built it 1335 p.c.

-

Excerpts from notes concerning the events from July 16 to July 22, 1930

-

Wednesday July 13, 1930

Nothing new has occurred today other than updates from Fez which, by the way, accentuate the extremely dire situation now that the popular masses are aware of the danger to our ethnic and religious unity posed by the enactment of the (Berber) decree.

The youth of Salé held a meeting today and conferred with El Yazidi. They decided to send a delegation tomorrow morning to meet with Mr. Benazet, Director of Indigenous Affairs to inquire about Abdellatif Sbihi's status.[9]

-

Thursday July 17, 1930

This morning, the designated members of the Salé delegation, Mohammed Chemao, Abdelkrim Sabounji, Kacem Hassar and Abdelkrim Hajji met with the Director of Indigenous Affairs in his office. They received a warm and courteous welcome. However when they inquired about Abdellatif Sbihi, he insisted they speak first about the Berber issue. As soon as he began his preamble on the issue, they realized that he was seeking to justify France's stance on the matter. They were told that France appreciates and respects Islam and would do all in its power to protect and preserve it. He then advised them to suspend the protest movement until the Sultan returns home (from France). In turn he pledged on his honor to fully review the issue at length. This turned out to be an empty promise for the discussion hardly encroached upon the boundaries of political credibility as the director went on to distort the truth as he saw fit. The discussion lasted two hours covering all the key political and religious issues. In return for suspending the protest movement and supporting the administration's actions, the members were told they could expect to be rewarded with high position jobs.

As far as Abdellatif Sbihi was concerned, Mr. Benazet initially informed them that he was to be referred to the Pasha of Marrakesh. Then he retracted this statement saying instead that the accused was kept in isolation due to the protest movement's serious provocations to law and order. He was accused of being the instigator and would be held to account for his actions by the appropriate authorities. Judging by these comments, it appears that the Protectorate Government is still undecided on what to do with Abdellatif Sbihi and, in the interim, he would be exiled in Marrakesh for an indefinite period.

News about the meeting between the Salé delegates and the director first spread across the cities of Rabat and Salé then it propagated beyond. We successfully fulfilled all of the goals we set for ourselves. After the Friday prayers, we collected a vast amount of alms to meet the needs of the poor. Moreover we were able to create a surge of national awakening and instilled a deep sense of solidarity among our people. Moroccans now consider the movement's initiators as its true political leaders.

The youth of Fez dropped everything they were doing and set in motion their own protest movement in Fez. They also asked Abdeslam El Wazzani to give a speech on their behalf at the end of the Friday prayers.[10]

-

Friday July 18, 1930

Public opinion was totally focused on the Berber Policy issue. The Latif Prayer (a traditional plea for mercy against a calamity, in this case the calamity was the Berber Decree) was invoked in six mosques in Rabat. Alms to the poor were distributed in some. In Salé, the Latif Prayer was recited inside the Grand Mosque while alms were distributed in all of the city's mosques. Large crowds gathered and voiced their solidarity with the cause.

In Fez they had never experienced such excitement before. After the traditional prayers the faithful were asked to rise and invoke the Prayer for Mourning. Then they recited in unison the Latif Prayer. Afterwards Friday's designated speaker, Abdeslam El Wazzani, walked up to the podium in the center of the mosque. He received a standing ovation and wild enthusiasm as he re-invoked emphatically the Latif Prayer. He followed by giving a speech dotted with patriotic slogans all of which had a common theme, unity to confront the Berber crisis. He proceeded to analyze in detail each of the articles of the Berber Decree of May 16, 1930 and put into perspective the dangers to our nation if this law in enacted. He told the congregation that this law aimed to divide the nation. Under the guise of an alleged reorganization of the justice system, it sought to replace the Islamic laws proscribed for all Moroccans be they Arab or Berber by pre-Islam Berber customary laws (to be applied to the Berber segment of the population). Abdeslam encouraged faithful to go in mass to the Moulay Idriss Mausoleum where Mr. Sefrioui would give another speech on the crisis. This would be followed by an open discussion led by Hachim Filali on the key themes of the speech. As the crowd was heading to the new gathering, they got word that the Mr. Sefrioui had been arrested by order of the Pasha. All out of sorts, they ran to the Pasha's residence where they were informed that the rumor was not true. Shortly afterwards, Mr. Sefrioui was sighted coming of his own freewill from the city. Relieved, the crowd began to disperse. But as they were leaving the Pasha's residence, an altercation broke out between a young patriot and a law and order officer. Fistfights ensued. The Pasha intervened and ordered four youths be thrown in jail and whipped in punishment. Later that day he arrested twenty additional youths who were among the organizers of the demonstrations. The residents of Fez spent the evening with mounting tension as all kinds of rumors spread about extremely severe repressive measures that were being used to intimidate the townspeople.

-

Saturday July 19, 1930

The youth of Salé and Rabat were informed early this morning that Abdellatif Sbihi's[11] mother would speak with the young freedom loving men to encourage them in their patriotic endeavors.

That night, we had planned a gathering to invoke the Latif Prayer at the Grand Mosque of Rabat. At the appointed hour, youth from all social strata, filled the huge interior of the mosque. Readings from the Koran led to deep meditation. Afterwards the Latif Prayer rang out from the chests of all present.

We then proceeded to Mrs. Sbihi's home where we were welcomed very warmly. The youth of Salé and Rabat took this opportunity to share with each other their latest undertakings. At 6:00 PM we gathered in the inner courtyard to hear the speech by Mrs. Sbihi outlined below:

"I wish you, my sons, a wonderful evening. My most sincere wish is that you are in good health and to hear reassuring news from each of you on your well being. How do you feel about the arrest of Abdellatif? I, for one, am very happy and proud of the struggle you are waging to defend our country and its religious values. May Allah help you in your quest and give you strength to continue your resistance (to injustice) and your readiness to serve your nation. I am pleased that my son is part of your movement. His arrest is for a just and noble cause that you champion. This is a cause to which I am prepared to give all of my all best, even it if means to sacrifice for my country all that I have; including my own sons.

My sons, do not spare any effort to serve your country and religion. Allah is with you. Have no fear and you will not be victims of setbacks or irreversible failures in your endeavors. To die for one's country and religious values is infinitely better than leading a life of humiliation and indignity. Have no fear. There is only one death and heaven's gates are wide open to welcome freedom fighters like you. Know that Allah awards men who have shown persistence. You can count on Him to provide you with the faith which moves you and with the commitment to your values that will bring equity and justice to our nation."

She had hardly finished speaking when the faces of the audience were filled with wonder and joy as if they were saying: What a great omen for Moroccans to have such a woman who brings honor to the women of this country. May Allah grant that all men be inspired by her will, her determination and her faith. Otherwise it would be very difficult for them to have the needed drive to act and to accomplish their mission!

At night new rumors circulated on the events that had occurred in Fez. These however we have already mentioned yesterday.

-

Sunday July 20, 1930

The news of the events in Fez reached far and wide across the nation, despite efforts to stem its spread. It is gratifying to note that the news has fed the popular masses with increased determination. Buoyed by the will shown by the protesters in Fez, they firmly redoubled their efforts to do all in their power to resist oppression. We are told that all they could speak of was the heroism of the youth of Fez . They even chided us for not joining them in jail. These same sources inform us that the protests are ongoing. The people invoke the Latif prayer repeatedly and there is no dissension amongst their ranks.

Meanwhile Salé's youth went door to door to inform the town's merchants and workshop owners that the Latif Prayer was to be recited at the Grand Mosque during today's afternoon prayers. By 4:00PM the mosque was literally overwhelmed by the attendees whose number was assessed to exceed four thousand souls; an impressive number with respect to a town like Salé. It was noted that a large contingent from Rabat attended as well. The gathering began by reading a few verses from the Koran followed by the afternoon prayers and several (traditional) pleas to Allah. The session ended after the Latif Prayer was recited in unison by all attendees.

On this occasion, an attendee had conceived a new verse whose first hemistich ended with the word "El Latif" which means "Allah the Merciful" and the second hemistich ends with "Abdellatif" meaning "servant of Allah the Merciful". This verse which associated one of the attributes of Allah with the name of the exiled leader goes as follows:

Have pity on your subjects, Oh Allah! Oh El Latif!

May you command the liberation of AbdellatifThe echos of the Latif prayer resounded from all four corners of the town. Upon exiting the Grand Mosque, we went to the beach (nearby) and discussed the current political and social crises. In the evening Salé's youth reconvened with El Yazidi and Abdellatif Laâtabi in the residence of Number 75.[12]

Many topics were debated during this meeting but the most dominant was the problem posed by Abdellatif Sbihi's exile. Number 75 proposed that a delegation of youth from Salé meet as soon as possible with Mr. Bénazet's Department of Indigenous Affairs to inquire about the fate of the exiled leader. The proposal was reviewed and endorsed by the attendees. A committee, whose members were selected from those present was set up immediately. Its members were El Yazidi, Chemao and Abdelkrim Sabounji.

-

Monday July 21, 1930

Abdelkrim Sabounji was bedridden so only El Yazidi and Chemao were able to meet with the Controller of Public Order for the province of Rabat. They discussed at length the Berber issue, it being central to the exile of Abdellatif and hence to their visit. The regional head requested that they refrain from inciting the people and assured them that their demands would be given due consideration. Unfortunately these words were those of a politician whose intent was not creditable. At the end of their meeting, he let them know he would contact the Director of Indigenous Affairs and get an update on the status of Abdellatif. He promised to contact them with the results of his inquiry on Tuesday.

In the afternoon, Chemao visited the Controller of Public Order of Salé under the pretext to talk about the availability of an Egyptian magazine which the government had mistakenly assumed was pulled out of circulation a few days earlier.[13] Chemao turned the discussion to the Berber issue. After a few hours of dialogue, he learned that the government had resolved to amend article 6 of the Berber Decree. He reached this conclusion after informing the Salé official: "This morning El Yazidi and I met with the regional Controller who assured us that the decree was to be repealed to our entire satisfaction as soon as the King returns from his trip to France." The official, taken somewhat by surprise (that they had met with his superior), responded: "The decree will not be repealed, only the article 6 will be amended."

Cornered, the official, let out this detail thinking that must have been what his superior had passed on to them. He also explained that perhaps the government felt awkwardly about the whipping inflicted upon the Fez youth. He added that the Protectorate Authority does not condone corporal punishment imputing it was cruel and barbaric and that it would remind the Pasha of Fez of their position on this matter.

-

Tuesday July 22, 1930

Nothing newsworthy today. All is well as can be hoped for. People have begun to sense some hope that the decree would be repealed. The regional office let El Yazidi know that they would allow an immediate family member to visit Abdellatif in Marrakesh after obtaining authorization from the Controller of Public Order of the district of Salé. There is nothing of substance to report on the situation in Fez. There are unconfirmed rumors that the government tried to free El Wazanni but he allegedly refused to leave until all other detainees were freed as well.

-

-

Excerpts from memos from July 4 to July 22, 1932

The members from Fez decided to commemorate the anniversary of the big protest demonstration that led to the arrest and beatings of young participants by order of the Pasha. They distributed leaflets on the eve to remind the people of the solidarity they expressed back then. They also attached posters to walls throughout the city. This distribution of leaflets and posters was confined to the city of Fez. Ibrahim El Wazzani was amongst the youth who volunteered for the operation. He was caught red-handed and marched off to prison where he is being tortured to this day. They subjected him to lashes with a whip demanding the names of his comrades. However he showed great fortitude of character and courage by refusing to divulge the names of his fellow compatriots. This further inspired and reaffirmed the will of the youth to bear whatever sacrifices needed to defend their convictions and their attachment to the values of freedom and dignity.

From that day forward, Fez was like a city under siege. Everyday at dusk a general curfew was imposed. A number of people were arrested for unjustified and insignificant trespasses. The authorities tightened their control citywide. The slightest suspicion led to arrests and mistreatment.

One can cite for example the case of a taxi driver who was shot dead because he had failed to stop at the injunction of a police officer. The law and order official claimed that he could not trust the driver. The next day, the (colonialist) newspaper reported that the driver was caught while climbing the outer wall of the Regional Administration compound. They had totally distorted the truth to cover the criminal act perpetuated by the officer who deserved to be prosecuted and punished. The driver is now the first fatal victim of the protest movement against the Berber Decree.

Another example was brought forth by the arbitrary arrest of a public school teacher, Bouchta El Jamii[14] whose crime we are told was that he believed in the patriotic ideals and had many friends in Fez. He refused an offer to become a court clerk at some unspecified location preferring imprisonment over the glimmering mirage of the bribe which would remove him from Fez.

Upon returning to Salé, I asked my friends for updates on the latest developments and found out that a new association was hatched to perform a number of (nationalist) activities. After reviewing the ways and means to strengthen the foundations of this group, I made several recomendations which were immediately adopted. We agreed to hold several meetings to develop a plan of action for a first phase focusing on the following items:

-

Creation of a national fund

-

Establishment of ties between Moroccan youth and their counterparts abroad

-

Adoption of a national alliance

The first item was the first order of business in our meetings and (subsequent) reviews allowed us to explore two means by which we could raise money for our national fund:

-

Sale of books or other merchandise that would awaken the patriotic fervor. Suitable pricing will be set build the fund from the realized gains obtained by the sales.

-

Solicitation for monthly donations from active members and affluent members of our society. We have composed a comprehensive list of potential donors and each of us will contact neighbors and the circle of their acquaintances.

During the day of July 14 we received news that El Yazidi, Sbihi and Al Attabi were granted amnesties. That night, El Yazidi's father received a cable from his son announcing his return. Al Attabi's wife also received news of the return of her husband. We were overwhelmed with joy. The next day Al Attabi and El Yazidi arrived at 3 PM and 10 PM respectively.

We were totally unaware of the circumstances which led to setting our colleagues free. But once we met with them, we learned that the Controller of Public Order met with them on Friday morning and informed them that they were free to return home. He showed them a telegram from the French General Residence in Rabat granting them amnesty in honor of France's July 14 national holiday. Later we found out that the decision to free them was made by the French National Government and not by the administration in Rabat. It was next to impossible to meet face-to-face with El Yazidi during the first four days of his return as he was with family and close friends.

One week after their return, they met with the Controller of Public Order for the province of Rabat who expressed his joy to meet with them. But when they asked him about the Berber issue he replied that he was not able to discuss this with them. Furthermore he said that the Director of Internal Security wished to speak with them that day but was unable to do so because of a last minute urgent request to go to the General Residence. Accordingly their meeting was moved to the next day. They waited an hour past the appointed time before the Director led them into his office. He began the discussions with an intimation that he would like to approach them about offers for future employment in the civil service. He then directed his attention to El Yazidia and said,

"Your father is very concerned about you. You need a lot of rest and quiet."

"Yes, it's true," he replied, "I plan on taking two months of rest."

When El Yazidi diverted the discussion (back) to the Berber issue, the Director of Internal Security tried to downplay the issue as if from his viewpoint it was of no import. And each time El Yazidi pushed on the matter, he dodged the issue.

Finally patience ran out and the meeting proceeded as anticipated by the (suspicious) nationalists. The Director declared that the Protectorate Government had promised the Berbers to do all it can to safeguard their practices and customs and it would be out of the question for it to fail to meet this commitment. El Yazidi retorted that the Berbers have more important demands than the preservation of outdated traditions.

At this point, the Director showed a document His Majesty the King had submitted to his Berber subjects given them the choice between a justice system under an Islamic magistrate or one from their tribal assemblies.

El Yazidi responded, "Then why were the representatives of the tribes who responded to the King with their wish to remain under the Islamic law sent to prison?"

The Director of Internal Security, tired of arguing, replied that the representatives of those tribes were unstable and each day came back with new grievances. Then he made it known that the government was not in any manner going to be influenced by public pressure. Moroccans, he added, need to demonstrate patience. The King would probably amend the decree on his own but it would be impossible to make that decision in a tense climate as exists today.

El Yazidi then took on the issue of teaching Arabic to the Berbers but the response was a categorical "no" under the pretext that the Berbers refused to learn Arabic.

In conclusion, it can be said that nothing constructive came out of this meeting and that the Director tried (in vain) to conceal the true intentions of the protectorate establishment. We are completely convinced that even if the Protectorate Authority wished to modify its Berber policy, including altering the contents of the decree, the position taken by the Director with respect to El Yazidi's inquiries would remain the same. Otherwise he would appear weak and lacking resolve.

Following the session with the Director we held a meeting (at El Yazidi's) to decide the terms and the means of our future course of action. Unfortunately, we were constantly interrupted by the flow of relatives and friends so we were not able to come up with practical solutions to the task at hand. Hence El Yazidi, Omar ben Abdeljalil and I left the house to continue our meeting away from the visitors.

As we walked we laid out a plan of action which included items to be carried out internally and abroad. Each action item would be studied carefully with input from others. Omar ben Abdeljalil would solicit recommendations from our Fez colleagues. Meanwhile we three would study the ways and means of implementing the action items. The results of the study would then be presented to the appropriate townsfolk for their review. Finally representatives from each city would attend a plenary session to debate (the pros and cons of) the recommended solutions and to establish a common consensus.

After agreeing on this plan we parted company around midnight, Friday July 22, 1932.

-

-

Excerpts from memos dated July 26 and July 28, 1932

-

July 26, 1932

Today I rode up to Rabat where first of all I met with Driss Albnioui.[15] Our discussion focused on the attempts by the French (Administration) to rally to their cause a number of influential (Moroccan) notables. The French wanted the notables to use their charm to improve the relations between the administration and the governed. The public mood was sour and spreading like wildfire across the nation. However when the notables inquired about the Berber issue, the French tried to sidestep this topic stating that this was a settled matter since a final decision was reached that conformed to the wishes of the Berbers.

Afterwards I met with El Yazidi at Rabat's main park and discussed two contradictory pieces of information with regards to the turmoil in Fez.

First it was said that the Fez youth had hired a lawyer to defend Brahim El Wazzani. The latter demanded the government of France to pressure the Resident General in Rabat to free the defendent so he can get proper hospital treatment. A rumor spread saying he was hospitalized while another announced his death.

Secondly word reached us that Brahim El Wazzani, after refusing to divulge the names of his colleagues finally broke down under stress and confessed his relationship with each of them. He allegedly said that he received the leaflets through Mékouar who was under British protection. Mékouar in turn received them through Haj M'hammed Bennouna of Tetouan. Going up to the top of the chain, the leaflets were said to have been conceived in Geneva by Mohammed Mekki Naciri and by Mohammed Hassan El Wazzani and released to Ahmed Balafrj in Paris who then shipped them to Tetouan. I quickly informed El Yazidi that this was a baseless rumor and pure slander. The leaflets never went through the chain described in the alleged confession by El Wazzani. This was another incredible lie by the government fabricated for some hidden purpose. El Wazzani is a friend and I know he has no contacts abroad and is completely unaware of Moroccans who deal with the outside world.

When we arrived at El Yazidi's home, we updated each other on the latest developments with respect to the May 16, 1930 Decree. I brought to his attention the fact that those who were granted amnesty could be pushed to abandon the struggle while their comrades would stand firm on their principles. El Yazidi in turn let me know that he had visited with the head of the urban affairs of Rabat to inquire about the intentions of the Protectorate Government with regards to the Berber Decree. However the latter refused to add anything more than what was said by the Director of Internal Security.

El Yazidi was out of touch on the events that occurred in Morocco and abroad during his exile so I gave him a brief picture of what happened in Salé and the recent activities of its youth. I also recommended that he meet face-to-face with Driss Albinioui who has firsthand knowledge on events that occurred in Rabat and to contact our friend El Fassi for news from Fez.

We agreed to continue to ponder what can be done about the Berber issue and, after El Fassi returns, to make a final decision on the actions to be taken in Morocco and abroad. I also suggested that he stop any dialogue with the representatives of the Protectorate Government until after the Resident General's [16] trip to France. If he is dismissed or simply relieved of his duties then we will know that either the French national government will completely change its tactics or at least is resolved to review and improve its interventions in Morocco. However if he remains in office we will know that France's intentions remain unchanged. Then it would be up to us to react accordingly using the appropriate means in support of our struggle. Furthermore we must not lose sight of the need to immediately seize this opportunity to broadcast widely in France the events (and turmoil) in Fez, the protest movement against the Berber Decree and the Moroccan Bill of Rights.

-

July 28, 1932

The El Wazzani Affair

Yesterday, our friend, Hachmi Filali came to Salé. We took on several topics not the least of which was the El Wazzani Affair. We were informed that during the first three days of his detention, the authorities put pressure on him to divulge the name of the other person who had been distributing leaflets with him. Confronted by his obstinate silence they decided to accompany his interrogation with beatings with a whip.

He appeared before the Pasha had a hearing and then all government staff were excused. Only the Pasha and the security officials charged with carrying out the cruel beating remained with the accused. But he had such strength of character that he was able to withstand the physical abuse inflicted on him and he refused to make the confessions they wished to extort from him. Despite all the efforts by the authorities to keep the news of the whipping from becoming public, it spread like lightning the instant he was being punished ruthlessly. The public mood was deeply agitated, the whole society's outrage was at a climax. Thanks to his unshakeable will and foolproof sacrifice El Wazzani behaved in an exemplary manner. He brought honor to the Moroccan youth by not being intimidated by the acts taken to make him talk. Neither the lashes he received across his body nor the blows that rained down on his head and face overcame his will to remain silent. In fact, he seemed to say, "Come what may!"

(To stop the lashes) they suggested that he conjure up all sorts of accusations that would lead to the arrest of his comrades. He replied with much irony in his voice, "If you absolutely must have me tell lies, I know of no one other than yourselves, against whom I should take that privilege,"

The young activists of Fez wrote a letter of strong protest to the French national government and to the League of Nations. The text of their indictment was published in a number of international newspapers. It was distributed to all chancelleries as well. Moreover a lawyer was commissioned in Paris to defend the 'accused'. He immediately addressed a telegram to the French Resident General in Rabat requesting all information related to the charges against his client so he can put together his defense dossier.

We are sure to see more news on this affair in the coming days.

The Abdellatif Sbihi Affair

On July 13 amnesty was officially granted to Abdellatif Sbihi and Mohammend El Yazidi but Abdellatif was not informed by the regional head of Tiznit until the 19th. The latter was using the extra week of detention for endless attempts to convince Abdellatif to cease his involvement with the protest movement against the Berber Decree. However, Abdellatif categorically repulsed all these attempts with some irritation and resentment. Finally he told the regional head that he had no intentions to cause any social disruption but that he would seek legal means to oppose the (French) Berber policy.

Abdellatif sent an envoy to his brother (Abou Bakr) in Casablanca to bring back news of the latest events and to find out if his comrades had renounced continuing the struggle as claimed by the regional head. (In addition the regional head had tried to lure him with an important position within the administration bureaucracy.) When his brother was informed of the purpose of the envoy's visit, he immediately returned to Salé. I met with him and promised to clarify the matter with El Yazidi. That same evening I went to El Yazidi's home in Rabat where he assured me absolutely that he had not renounced the struggle. Like Abdelllatif, he only promised his jailers that he would pursue his focus on the Berber issue within the law and that he would not disturb the peace. Futhermore he informed me that the French (authorities) were harassing him with hiring offers and the only reponse he gave them was that he was in need of much rest after all that he just went through.

I returned to Salé and informed Abou Bakr Sbihi, about my meeting with El Yazidi. We agreed that he would report verbatim El Yazidi's words to his brother and to ask him to inform us about the position he will be taking. The response from Abdellatif came back in short order. He immediately aligned his viewpoint with El Yazidi's and told the regional head, "Our comrades have resolved to pursue legal means for our cause. Furthermore we assume that any hiring proposal is a personal matter which is not tied in anyway to the patriotic cause that led to our exile."

And that is how Abdellatif continues to stay in Tiznit and that it is not possible, under these circumstances, to predict what will happen next.

-

-

Excerpts of memos concerning certain events in 1933 and 1934

In addition to the Al Maghrib magazine written in French which was circulated in Paris, other newsprint appeared during the summer of 1933. These included L'Action du Peuple (The People's Action) published in Fez and the Assalam (Peace) magazine and the Al Hayat (Life) and Al Houria (Liberty) newspapers in Tetouan. They fulfil their role as opposition newsprint and never fail to severely take issue with the direct policies of the (French) administration that the Protectorate authorities attempts to establish in Morocco. They received encouragement by way of the awakening of the nationalist fervor of the Moroccan people and their awareness of self-hood and by the conflict between the Resident General Henri Ponsot by the French settlers. They understood that Henri Ponsot favored radical reforms to the administrations apparatus despite the silence surrounding his efforts. For sure he was not in conflict with the leaders of the National Movement but he abstained from following up on their demands. He responded with the same reservations to the French settlers including remaining deaf to the attempts by the Department of Indigenous Affairs to shut down the nationalist newspapers and their attempts to carry out a repressive policy against the National Movement.

In early May, the Department of Indigenous Affairs took advantage of Henri Ponsot's trip to Paris to hatch a most absurd plot which was carried out despite its stupidity. The administration had not been pleased to see His Majesty the King receiving so much enthusiasm during his visit to Fez. nor with the fact the King had met (publicly) with an important delegation of the National Movement at its entrance. It found it intolerable to witness the unprecedented sea of humanity greeting the King with jubilant cheers, giving free reign to their patriotic feelings and demonstrating their adulation for him as a symbol of liberty and a guarantor of national unity. Faced with the surge in nationalist fervor and under the pretext that a French flag had been ripped apart by some demonstrators, it shut down The People's Action and blocked the newspapers from Tetouan (in the Spanish zone) from entering the southern zone (under the French protectorate). This act led to the King to interrupt his trip to Fez where he had hoped to stay for one month as was customary. He made this decision to show his displeasure with the actions of the colonialist authority.

Upon his return to Rabat, he had his Grand Vizir invite Allal El Fassi, Hassan El Wazzani, Omar Ben Abdeljalil and Mekki Naciri. The Grand Vizir also conveyed the King's great esteem for them and that they stood in his good grace.

[9] The protest movement against the Berber Decree was launched in Salé with the Latif Prayer recited in the Grand Mosque. Abdellatif Sbihi, a civil servant in the Direction des Affaires Chérifiennes (Department of Religious Affairs), distinguished himself in the struggle against the Berber policy of the French Protectorate which surfaced with the Berber Decree of May 16, 1930. He was dismissed from his job, exiled to Marrakesh and later moved first to Tiznit and then to Azilal. By banishing him, the French thought they could put an end to the protest movement and to the gatherings where the masses expressed their indignation by way of the Latif prayer. However his exile only ignited further passion among the patriotic youth and intensified their acts of resistance. The mosques of Salé, Rabat and Fez were filled to capacity by the faithful who rejected the colonial settler's political aims to divide the nation.

[10] Abdeslam El Wazzani was a pioneer of the National Movement in Oujda. He was very effective in the struggle against the colonial policies which earned him a lot of time in jail. After independence he served with distinction as a judge.

[11] Mrs. Aïcha Sbihi, daughter of Haj Ali Zniber. Haj Ali was one of the first to awaken to the French colonial designs over Morocco and wrote a series of recommendations to Sultan Moulay Abdelaziz. He also submitted to the sovereign ruler a draft of a constitution. The Sbihi Library in Salé contains several handwritten manuscripts of note by Haj Ali. His daughter and mother of Abdellatif Sbihi, was cited for her courage and patriotism. After her rousing speech to them, the youth of Salé fondly called her "the mother of Moroccans."

[12] No 75 was Mohammed Chemao, a member of the "Al Widad" society, whose members used numerals to sign their writings and letters so as to remain anonymous. Said Hajji was assigned the number 25 (see for example in this series, the letter from No. 25 to No. 75).

[13] Chemao owned a bookstore in Salé which sold Arabic magazines and newspapers.

[14] Bouchta El Jamii was another pioneer of the National Movement. He was one of the first patriots subjected to imprisonment and torture during the colonial era.

[15] Driss Albnioui was a nationalists who contributed to the rise of the patriotic movement in Rabat. His shop, a regular meeting place for the young patriots, was considered like a club where they could exchange ideas and comment on the national events of the day. It was also the central point for the distribution of leaflets.

[16] Resident General Lucien Saint tried to accelerate the enactment of the Berber Decree of May 16.