We encounter several difficulties in the restitution of the genealogic tree of Said Hajji's family. One of the most significant of these difficulties is due to the short memory of the present generation of this family which hardly goes up beyond the second half of the seventeenth century and ends with the installation in Salé of the first known of its forefathers, the venerable Ahmed Hajji whose disappearance dates from the 7 Rabia 1 - 1103 according to the hegira calender (November 28 - 1691). Some trace his lineage many centuries back to Sidi Bouazza, who came down from Moulay Idris, the founder of the first moslem dynasty in Morocco. Some others say that his marriage certificate, established during the reign of Moulay Ismaël, which could provide valid informations on his ascending, is to be found among the documents preserved by the well known historian of Salé, Mohamed ben Ali Alsalawy. Apart from these summary indications, which require to be checked and documented before granting them any credibility, we remain in a total ignorance of the actors of the former generations. We know neither their first names, nor where they did come from, the ones making them go up to the idrisside dynasty, as it just has been mentioned, others arguing that they might have come from Spain during the period of the reconquest of Andalusia, and some others thinking that they were originating from Tunis and they established in Morocco after having initially settled in Tlemcen for a while. Though these indications seem worthy to be investigated, they remain simple conjectures on which it is hazardous to achieve a reliable statement, at least as long as they are not clearly stated by public or private archiv documents attesting or denying the authenticity of the versions advanced by all and sundry on the basis of an oral tradition in their respective milieus.

- 1 -

In this order of ideas, we can underline the existence of a certain Ahmed Hajji, who lived in the sixteenth century and could have been one of the forefathers of the venerable saint of the same name who rests in the mausoleum which was built for him in Salé. Ahmed Hajji the older one - if we may attribute him such an appellation - was a personality of an exceptional level of culture. One owes him the famous chart of the world in form of a heart, known under the name of "Mappamundo of Ahmed Hajji" which he conceived during his captivity in Venice and let draw in 1559/60 by an italian cartographer to the attention of the sovereign of the Ottoman Empire. According to the text accompanying the chart, initially written in arabic and then translated into turkish for the "Sublime Porte" by Ahmed Hajji, the latter has described himself as "a moslem scientist, originating from Tunis, having persued his studies at the university of Fès, and having been captured later by the infidels."

The orientalist Pekka Masonen, from the history department of the finnish university of Tampere, wrote these lines about the scientist Ahmed Hajji in an article which was published in 2002 in "Al Andalous-Magreb," vol.VII-IX. f.1 p.115-143, under the title "Leo Africanus, the man with many names:"

"Leo's willingness - so the author - to collaborate with the enemies of his coreligionists was neither unique nor (giving) any indication of his opportunistic character. Some 40 years later, in 1559, we hear of an other north african prisoner who also agreed to pass his geographical knoweledge of the islamic lands in the Mediterranean to the hands of his christian captors. This was a certain Hajji Ahmed whose fate resembles curiously that of Leo. Ahmed was from Tunis, but he had studied at Al Qarawiyyiyn in Fès, before he was captured and sent to Europe, more likely to Venice. There, he prepared a planisphere covering Europe, Asia, Africa and the known parts of America while in the custody of (a virtuous and learned gentleman). According to Ahmed Hajji, he was promised freedom in exchange of his knoweledge."

Professor Benjamin Arbel, from the historian department of the University of Tel Aviv, who was cited by the oben mentioned finnish orientalist, devoted an article of ten pages to the history of the world map which was conceived by Ahmed Hajji. This article, dated November 2001, was published in No 54 of the international history review of the cartography "Imago Mundi" - London - under the title "Charts of the world for Ottoman Princes - Other evidence and questions relating to the map of the world of Ahmed Hajji."

The author of this very documented study was interested by the work of this great scientist, who was a continuum of Mohamed ben Hassan Alwazzan, more known under the pseudonym of "Leo Africanus," geographer and cartographer like him, having both of them been captured at a few years of interval, in the same circumstances and for the sames purpose by the italian corsairs. The only difference which distinguished the two men was that Leo has been led to the Vatican and was delivered to the Pope who put him under his protection in exchange with his scientific knoweledge, and Leo agreed to convert to catholicism in order to deserve the good graces of his Holiness who became his benefactor, while Ahmed Hajji was led to Venice to be placed under the authority of "the Concile of the ten" and the Venitian Senate. On the contrary of Leo, Ahmed Hajji wrote in the note of presentation of his world map that he was "a moslem scientist" and that he was "nourishing the hope that the efforts which he undertook to conceive the chart of the world would help him to recover his freedom."

For the rest, the conversion of Leo Africanus was without any doubt dictated by the single concern of profiting from a preferencial treatment as long as he was at the Pope's service. The proof of such an assertion which needs to be further verified, is given by the fact that, immediately after the Pope was dead, Leo Africanus regained Tunis, to die as a good Moslem and to be buried in the earth of Islam.

An other study made a few years ago by the italian researcher Antonio Fabris, based on new archiv documents, has rejected the claims of the cartographer Giustinian who tried to attribute to himself the paternity of the world map with the approval of the Concile of the Ten and the venitian Senate, 8 or 9 years after its realisation by Ahmed Hajji. This study does not let plane any doubt about the fact that the chart that Giustinian intended to publish in 1568 as if it were his property was the same as that one which had been produced in 1559/60 according to the inscription of this date on the chart itself, which remained during all this period in possession of the Council. The document on which the searchers have based their studies do not inform us about the other publications of Ahmed Hajji, if there were any, and do not provide any indication of what became of him after being released, if ever he gained his freedom after achieving the work whose realisation was entrusted to him by the city of Venice on behalf of the "Sublime Porte."

Considering the importance of Ahmed Hajji as an uncommon scientist, there is no doubt that further researches about his life and works may be full of interest to our historians who can follow his footsteps in the files of the university Al Qarawiyyin where he made his studies, before being captured by the infidels. These files may provide a mine of information which could help trace his lineage back and enlighten the milieu in which he lived during his stay in Fès as well as the disciplines which were taught at that time. They may also indicate if he left other scientific writings as well as the art of relations he used to have with his contemporaries. They probably contain useful indications about his preparations for the mission during which he was captured by the pirates of Venice. These documents can also inform us, insofar as they exist, if he left behind him a family awaiting his return. As many questions to which a meticulous study can provide brief replies and raise the veil on the possibility of the existence or not of a direct or indirect family tie with his homonym Ahmed Hajji who was established in Salé during the second half of the seventeenth century. Perhaps that this type of research is likely to interest some Tunesian or Turkish historians, in which case we will be most grateful to them if they could provide us with the results of their investigations.

- 2 -

It is very precisely established that the family of Said Hajji is issued in right hand from the lineage of the famous combatant Ahmed Hajji the second one, who had been particularly distinguished to have released the town of Mehdia on the atlantic coast of the spanish occupation in 1681 and died 10 years later, in 1691. Thus, and insofar as the investigations would lead to establish the existence of a family tie between the two Ahmed Hajji, 120 years only would have separated the date in which the chart of the world has been realised by Ahmed Hajji the old one and the battle of Mehdia led by the other Hajji who carried the same first name as well as the patronymic name as his predecessor. By taking into consideration the number of years the first had to live and the age of the second when he delivered the battle of Mehdia against the Spaniards, we do think that 80 years only had separated the birthdate of the latter and the date on which his supposed forefather died. Consequently, two to three generations only should have separated them, and as it is traditionally admitted to enumerate the ascending forefathers of a direct lineage in the marriage acts, we remain persuaded that the key of this enigma could be found in the marriage contract of the combatant Ahmed Hajji which is still preserved among the files of the above mentioned historian Mohamed ben Ali Alsalaoui, as specified by Haj Ahmed Maaninou in an article which was published in No 36 of "the Bouregreg Association Review" of Salé.

In 1681, the combatant Ahmed Hajji marched at the head of an army he raised in the plain of Chaouia, upstream of what will be later the town of Casablanca, and reinforced with 300 volunteers from Salé to launch out to the reconquest of the city of Mehdia. The battle turned in favour of the attackers, as the Spaniards agreed to leave the occupied city, but under the condition that their withdrawal will intervene in the presence of Sultan Moulay Ismaël in person. Ahmed Hajji has at once approached the Monarch to inform him of this condition posed by the occupying army. It did not last long that Moulay Ismaël went on the spot where was organised the ceremony of handing-over the keys of the city that the Monarch received from the hands of a spanish missionary. During this great ceremony which marked the end of the foreign occupation of the city of Mehdia, Moulay Ismaël offered to the combatant Ahmed Hajji a sword recovered from the enemy. This sword has been preserved by his descendants until the first half of the XXth century, and would have been given, so an uncontrolled rumor within the family, by one of them, Mohamed Faris Hajji, uncle of Said, to the great historian, Khalid Naciri, author of the most important historical reference book "Al Istiqsa." Thanks to this brilliant feat of arms, the Sovereign has honored Ahmed Hajji with the privilege of being venerated and respected all the rest of his life, and promulgated a "dahir of veneration" as a reward of his honesty and his bravery in the battle.

Ahmed Hajji owes both his prestige and his notoriety to his qualities of man of good, known for his integrity and considered as belonging to the saints of Salé. His mausoleum, located near the large souk, became an accurate aim of pilgrimage which attracts the people from all the parts of the city to gain its good graces. Moussems are regularly organised there. A large mosque was built near the mausoleum and became the main mosque at the large souk and the surrounding districts. The author of the above mentioned "Al Istiqsa" specified that Ahmed Hajji was the disciple of the sheik Abdallah ben Moussa. Preachings were lavished by his descendants who directed the collective prayers and animated the courses which were exempted within the enclosure of the large mosque. At the head of these descendants, came Abdallah Al Jazzar, in his quality of the eldest son with the moral right of primogeniture. This one was relayed after his death by his son Faris. Then it was the son of the latter, Al Mediane, who succeeded in the charge of directing the prayers and animating the courses. Sultan Moulay Ismaël charged him with the construction of the large mosque contiguous to the mausoleum of his grand father. After Al Mediane, it was the turn of his son Saidi to ensure his succession. After him came Harti followed by Abdallah who was the immediate grand-father of Said Hajji. Abdallah was a very learned man, and his courses in the great mosque of Salé used to attract a very numerous assistance. His son, Ahmed Hajji, was the first of the direct descendants of the saint forefather, to wear the same patronimic name as his ancestor.

"This family," wrote Ahmed Maâninou, "produced a significant number of cultured men and continues to be very proud of being a permanent hearth of culture and patriotism" . The same author believes to know that "the main profession of Ahmed Hajji was the manufacture of textiles, and that his methods of weaving had acquired a large celebrity in the city."

On his side, the historian Mohammed Zniber noted in his foreword to the Poems Anthology of Abderrahman Hajji, the eldest brother of Said, that, "among the descendants of Ahmed Hajji, many great men emerged; some of them were devoted to science and some others to commercial activities. Ahmed Hajji belonged to the last category, and was at the same time an experienced tradesman and a great patriot."

- 3 -

In his article previously quoted, which he entitled "A patriotic personality of Salé, the respectable and distinguished Ahmed Hajji," Ahmed Maaninou described Said's father in these terms:

"Born in Salé in 1865" - the author wrote 1885 by mistake - "died at the age of 96 years at the beginning of August 1961" - not in 1964 as specified in the same source - Ahmed Hajji was a worthy man and an enthusiastic patriot. He was at the same time an experienced tradesman who counted among the principle notabilities of the city and one of the most solid pillars of the National Movement.

He was a self made man who developed very early aptitudes for commercial activities. When his father was still alive, he used to go to Marrakesh to procure olive loadings that he transported on mulesback to the cities northward where he could sell his merchandise at prices which left him oft significant profit margins. He also used to buy standing wheat, which enabled him to constitute during the harvest time a reserve to supply his mills with grains and be the first in the market to sell the floor which he could highly rate in the absence of any concurrence. He also had a soap factory, a public oven to bake bread and cakes, moorish baths called hammams and investment properties which constituted the essential part of his incomes besides his interventions or arbitrations when the involved parts called upon his experience and know how in commercial deals.

The liberal activities to which he was devoted allowed him to constitute one of the most significant fortunes in his home town. He was in business relationship with the british market, and allowed his second son Mohammed, who followed private english courses which a lady from the british community in Rabat taught him at home, to settle in London at the head of a trade of import export. He tried to act in the same manner with his elder son, Abderrahman, whom he sent in 1928 to join his brother in the british capital to learn the wheel and deal of the business, but the latter, who was more inclined towards literature and poetry, spent the major part of his time composing poems which he dedicated to the circle of his friends in Morocco instead of filling his time by learning the secrets of the trade activities so that, after one year and a half, he decided to go back home in order to seek an occupation in conformity with his literary inclinations. His father, who was convinced that only the private sector enables to prepare to a life of responsibility, tried to settle him in any industrial branch of his choice, but he was disappointed when his elder son choose to be a teacher and started teaching in a public school since 1930. Ahmed Hajji was a clear minded man. While the country was living in the darkest era of its history, and was confronted to the policy of integration and linguistic assimilation imposed by the protective power, to the detriment of the arabic language, he refused to register his three younger sons, Abdelmajid, Abdelkrim and Said, in one of the lately created public schools called French Islamic schools, in which only the sons of the notabilities were admitted. He prefered maintaining them in the traditional schools with the possibility for them to follow private courses of arabic and english at home, as he intended to send them later on to the Middle East in order to pursue their studies in an educational establishment where the courses are teached in arabic.

When Abdelkrim initiated, with the support of his brother Said the movement of protest against the "Dahir Berbère" of May 16, 1930, their father informed them that they must respond to their act and instructed them to keep their head high and not to let themselves intimidate by the threats of the "contrôleur Civil" who was expected to seek by all the means to frighten them by the possibility to send them in prison and make them endure very bad treatments .

August 28, 1930. Ahmed Hajji was himself co-signatory of a petition adressed to His Majesty the King, to the French Minister of the Foreign Affairs and to the Résident Général of France to Rabat. By letter dated from the same day, covered of his and two more signatures, and bearing a list of some notabilities of the city, they requested the authorisation to represent the city of Salé to the audience which was going to be granted by His Majesty the King to the delegations of the nationalists representing various cities about the Berber Question, and to have the privilege to submit to his high attention the petition relating the deep indignation of the population of Salé.

December 11, 1935, one year after the day in which the "Book of the Claims" was presented to the King and the French Authorities, a telegram of recall emanating from the branch of Salé of the National Movement, signed by Ahmed Hajji and fourty other signatories, has been sent to these same Authorities.

December 11, 1936, a new petition was addressed to the Sovereign, deploring that the book of claims remained a dead letter and requesting the release of all the prisoners of the National Action Committee, victims of the consecutive repression to the events occured shortly after the royal visit to Fès which has been interrupted because of the unacceptable conditions posed by the representative of the French General Resident in Rabat.

Ahmed Hajji's house, a traditional moorish house with a very large patio which can contain an assistance of hundreds of people, was the ideal place to shelter the most important nationalist demonstrations as its owner inspired a certain respect to the French Authorities because of his relationships with the British higher dignitaries and his trade activities in the british market. The French have always considered him as a protégé of the british crown, which he never was; but the way he was welcomed in the United Kingdom each time he was attending the British Industries Fair, and the fact that he was received by the King George VI in person confirmed them in their conviction that he enjoyed a certain protection which made him untouchable.

Thus, while the french authorities were boiling with rage and the courts of justice were seized for any unsignificant reason and pronounced judgements on the basis of bills of indictment without common measurement with the facts complained of, was organized by Abdelkrim Hajji in his father's house on July 8, 1933, at the request of the National Movement, the commemorative ceremony of the first anniversary of the review "Almaghrib" which was published in Paris under the supervision of Ahmed Balafrej, and whose direction was entrusted to an influential member of the Socialist Party, Robert Jean Longuet. This review whose first number went back to July 1932, was created in the spirit to make hear the voice of Morocco abroad and in particular in France where it was assisted by a Committee of Support grouping political personalities, as well among the French politicians and deputies as originating from other European countries. The expenses engaged in financing such a review required the organization of periodic actions of collecting funds in which Ahmed Hajji took part, convinced that such a publication was the best means of serving the national interest in France and in the world.

The demonstration grouped all the leaders of the National Movement. Only Ahmed Balafrej and Said Hajji were absent from the meeting as the former was at that time in Paris and the latter in Damascus. Mohammed Hassan El wazzani pronounced a keynote speech and took stock of one year of activities of the review; he put forward the efforts made by the Committee of Support in favour of the national cause. Then, Omar Ben Abdeljalil took the floor to announce the project of creation of a second newspaper in french language: "L'action du peuple."

At the end of the meeting, a small committee was appointed to write telegrams to President Herriot, to Robert Jean Longuet as well as to the editorial board of the review in Paris.

The police spies always kept a watchful eye on Ahmed Hajji's house. They observed all the people who knocked at the door, wrote their name and quality as well as the day, the hour and the duration of each visit, tried as much as possible to get informed about what has been said between the guests and their host, noted the exact time of their departure and followed their steps to know where they were going to go thereafter. An illustration of this scenario is to be appreciated in one of the information sheets relating to the meeting of the nationalist leaders which was held in Ahmed Hajji's house on February 10, 1935, among the annex documents at the end of the book under the title "The Hajji family in point of test card of the general information" (Chapter 39)

Even the commercial activities were closely followed by the authorities of control, as it is clearly stated in "the political note" related to the promotion by Ahmed Hajji of the English trade in Morocco, which can also be read within the above mentioned chapter.

Georges VI et la Reine Elisabeth s'entretenant avec Ahmed et Abdelkrim Hajji - 1939

Ahmed Hajji et son fils Mohammed présentant leurs hommages à une grande dame de la Cour - 1938

Dîner de gala à l'occasion de l'inauguration de la Foire des Industries Britanniques - 1937

Ahmed et Mohammed Hajji parmi les invités au dîner de gala présidé par le Roi et la Reine d'Angleterre - 1937

During one of his multiple visits to London, he went to the head office of the B.B.C. to pay homage to the team of the arabic section for the excellent programs that many Moroccans punctually follow at the hours of emission intended for the listeners of North Africa. He was given an enthustastic welcome on his arrival, and the semi monthly review published by the Arabic Section of the B.B.C. gave an account of this visit in the following terms:

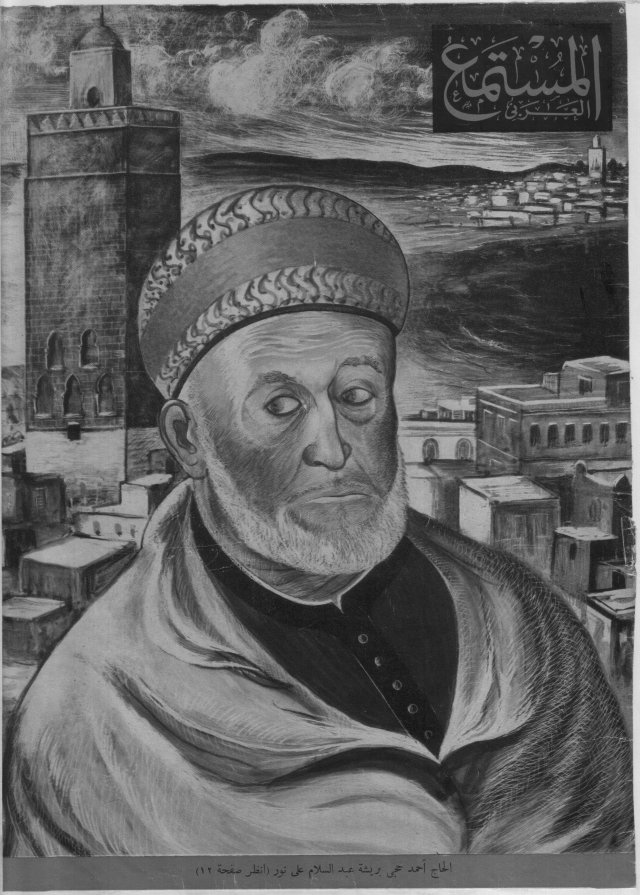

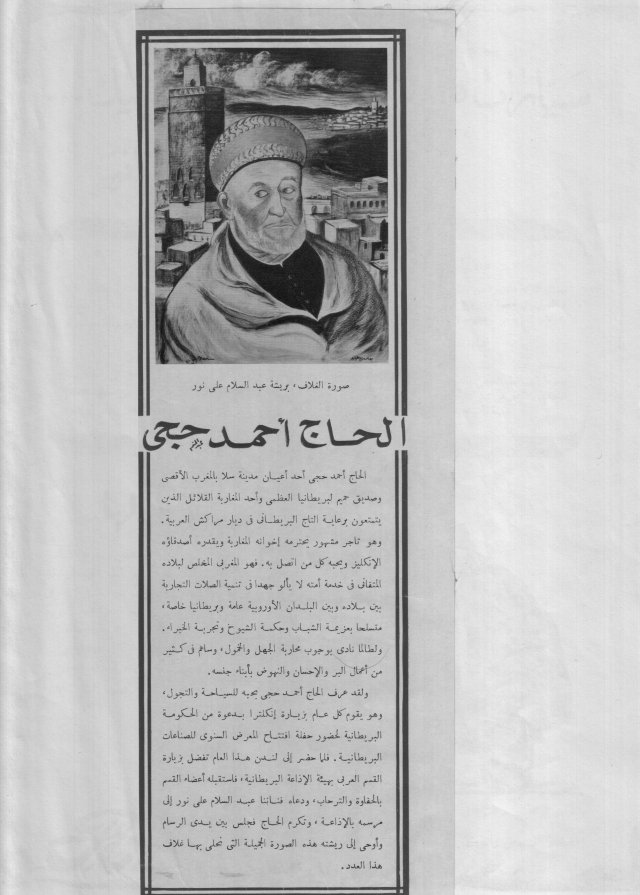

"Mr Ahmed Hajji, one of the notabilities of the city of Salé in Morocco."

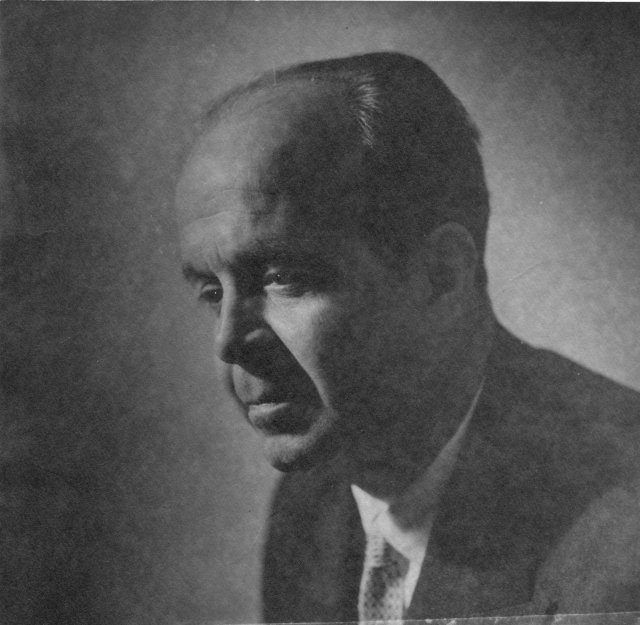

"He maintains friendly relations with the United Kingdom, and counts among rare Moroccans who benefit from the solicitude of the British crown in the Arab Maghreb countries. He is well known through his trade activities, respected by his Moroccan fellow-citizens, estimated by his English friends and appreciared by all those who came into contact with him. He is devoted to his country, does not hesitate to make the greatest sacrifices for the cause of his nation, and does not spare any effort to develop the trade of Morocco with the European countries in general and the United Kingdom in particular. His forceful arguments lie in assembling the will of youth, the wisdom of the third age and the know-how of the men of experiment. He is always exhorting his fellow-citizens to fight against ignorance and idleness, and takes part in many actions of benevolence aiming at raising the level of the children of his race. Ahmed Hajji is known for his predilection for travel and tourism. He returns each year to England to answer the invitation which the British Government addresses to him to attend the opening ceremony of the British Industries Fair. During his stay in London this year, he paid a visit to the Arab section of the B.B.C. where the members of this section reserved a gracious and cordial reception to him. Then, our artist-painter Abdeslam Ali Nour invited him to his atelier located in the same building, and realised this wonderful portrait of our guest with which we illustrate the first cover of this number."

Portrait d'Ahmed Hajji ornant la 1ère de couverture de la revue de la BBC destinée au monde arabe et intitulée "l'auditeur arabe" (vol.X No 13. 1949)

It has several times been said in this essay of description of the family environment in which evolved the Hajji brothers, that their paternal house was regarded as a real sanctuary of patriotism, where the nationalists organised the most significant of the political demonstrations during the Protectorate.

In this very house took place the large reception given by Ahmed Hajji in the honor of M'barek El Bekkai after his nomination to the Council of the Throne, nomination which had received the agreement of Mohammed V. This reception to which were invited the political parties and some representatives of the liberal oriented French who supported Morocco in its struggle for independence, had a political range which exceeded by far the framework of a simple civility. No agreement had yet been reached about the personalities who were to take part with Bekkai to the Council of the Throne. The Moroccan political parties which were engaged in the process of negotiations opposed their veto to the constitution of the Council as proposed by the Résident Général Boyer de la Tour, arguing that there was a risk of rupturing the balance with the suggested candidatures.

They clearly informed the French counterpart that they considered the Grand Vizier Mohammed El Mokri and the caid Tahar Ben Ouassou as representatives of the traditionalist side, and the pasha of Salé, Mohammed Sbihi, as a candidate who was committed neither on a side nor on the other. Taking these arguments into consideration, the President Edgar Faure requested Bekkai to go to Morocco in order to achieve the formation of the Council of the Throne. The reception organized in the residence of Ahmed Hajji took place while Bekkai was lodging at Mohammed Sbihi's, the pasha of Salé. It was probably during this reception that the decision was made to admit to the Council of the Throne Mohammed Sbihi and Fatmi Benslimane at the sides of Bekkai and Tahar Ben Ouassou.

Monday October 17, the Council of the Throne was installed solemnly in the Royal Palace where its four members were received by the Grand Vizier who read a proclamation specifying that the first task which fell on this Council was to form the first Moroccan government. One can thus read in volume 2 of the Memories of Edgar Faure published at Plon, page 577, under the title "A thaw is setting in":

"Bekkai obtained the agreement of Mohammed V and succeeds in thawing out the Democratic Party of Independence. The Istiqlal party, fearing to be overflowed, announced that it would not take part, but its reaction did not go beyond this formal announcement".

When Mohammed V came back from his exile in Antsirabé, Ahmed Hajji and his son Abdelkrim were among the first to go to Paris to renew to His Majesty their deep attachment as well as to the Alaouite throne. Then, the events were precipitated in the following order:

-

November 16, 1955: Triumphal return of Mohammed V to Morocco

-

December 7, 1955: Formation of the first government chaired by El Bekkai

-

February 15, 1956: Abrogation of the Treaty of Fès

-

April 7, 1956: Recognition of the independence of Morocco by Spain. The Spanish Government commits itself to respect the sovereignty of the country and its territorial integrity

Sa Majesté Mohammed V recevant Abdelkrim Hajji avec les membres de la délégation de Salé

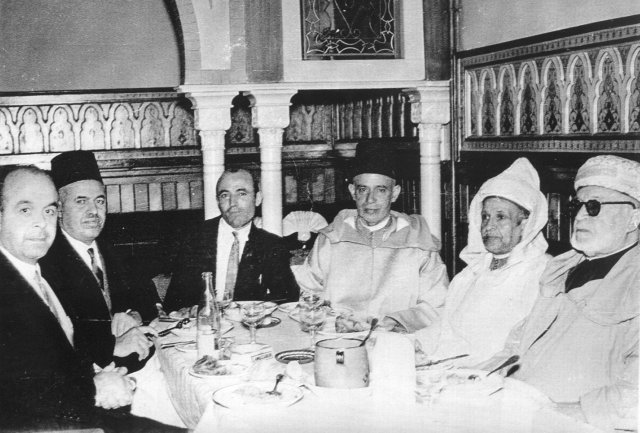

Les représentants de Salé venus à Paris pour exprimer leur indéfectible attachement au Roi Mohammed V après son retour d'exil. On reconnaît à droite de la photo Ahmed Hajji assis à côté de Moulay Taïeb Alaoui, et tout-à-fait à gauche Abdelkrim Hajji

Ahmed Hajji accueillant Mbarek Bekkaï au moment où celui-ci était appelé à faire partie du Conseil du Trône - 1955

- 4 -

The maternal side of the Hajji brothers

The mother of the young Hajjis, Fatma Msattas, is the daughter of the honourable Mohammed Msattas, who was given the same name as his father and belonged to the cultivated elite of the city. His father counted among the most important speakers of the mosque of Salé. The courses he professed attracted a huge circle of disciples and listeners.

In a biographical study having been used as foreword to the first edition of the Anthology of Poems of Abderrahman Hajji which goes back to 1991, the historian Mohammed Zniber made the following statement:

"... The Msattas family can be regarded as belonging to the families which completely disappeared today because of a break in the continuity of the male descendants. According to certain versions, this family was considered as one of the oldest families of Salé, as its origin went back to the era of Bergwata and Beni Al Ichra. It produced a series of men of culture, of which Mohammed Msattas father, who taught and commented on the work of Boukhari during the second half of the nineteenth century, was one of the most cultivated scientist of Salé."

His son must have been born about 1845 and died at the middle of the third decade of the last century, at the age of 80. Such an estimate is likely to be corroborated by a letter dated November 7, 1874, informing him that the Sultan has agreed upon his request to benefit of a scholarship from the budget of the Habous to allow him to end his studies.

A point of reference is provided to us by a letter sent to him from Médine on August 19, 1891 by a relative of Salé, Mohammed Lahrech, in which he wrote to him that he took note of the decision of his setting of availability and was happy to learn that he projected to come to the holy land to carry out his duty of pilgrimage.

Another letter dated January 28, 1904 teaches us that Ahmed Hajji, who married the daughter of Mohamed Msattas in 1889, had registered in the name of his father in law a property intended for gardening, separated from the gardens of the Doukkala company by a water pipeline,which he acquired at the price of 67 rials.

In a paper left by Omar Aouad which he entitled "a great figure among the personalities of Salé" he described the Msattas family in these terms:

"the circumstances wanted that the Msattas and Hajji families reinforce their friendly relations by reciprocal bonds of alliance. The residence of Msattas is very known in Salé. It is one of the large houses of this city which is characterized by its elegance and architectural design. It is located in a cul-de-sac, near the house of the historian author of the 'Istiqsa,' Ahmed Ben Khalid Naciri, giving on the street which carries out towards the mosque ". "It is probable that with his death, this family ceased existing in Salé, since the single boy that Mohammed Msattas could have is deceased at an early age and was not replaced by another male descendant to ensure the succession and thus the continuity of the family line. He was buried in a sanctuary in Salé, among great figures of this city such as Moulay Taib Alaoui, Ahmed Al Jariri, Haj Ali Aouad, Mekki Sbihi, the grand' father of the former pasha of Salé, Haj Driss Jaidi, to quote only some of the notabilities buried in the zaouiya of Derkaouas."

Saïd Hajji, 6 ans, avec son grand'père maternel Mohammed Msattas - 1918

- 5 -

Said the youngest of the Hajji brothers

The Hajjis as described on an information sheet established by the services of the Civil Control during the French Protectorate in Morocco, belong to a notable family of Salé, and are related to the well known families of the city: Sbihi, Aouad, Hassar and Msattas. The pasha of Salé, Mohammed Sbihi, and Ahmed Hajji are married with the daughters of Mohammed Msattas, which is true for the latter, and is the fruit of a confusion between the pasha and his half brother, Omar Sbihi, concerning the former. The same source contains two further errors, one concerning the name of the maternal grand father designated under the name of "Mefettech," the other about the projects of marriage of Abderrahman and Mohammed, both given like applicants to an alliance with the Aouad family, whereas only Mohammed planned to ally himself with this family, while Abderrahman, was projecting to marry one of the daughters of the Cadi of Salé, Abdelkader Touhami. A precision has been added as regards the single female figure of the family, Zhor Hajji, the spouce of Mekki Sbihi, the future successor of his brother Mohammed Sbihi as pasha of the city.

The information sheet provides the following indications on the five male children:

-

Abderrahman, "the eldest, 30 years old approximately" (he was 28), "young Turkish. Illiterate in French, but enough learned in Arabic. Single person. Without any employment. Lodged by his father. Stirring up spirit, always at the head of all the movements. Promoter of putting into circulation of a list of subscriptions in favour of the Moslems of Jerusalem during the last events in Palestine. Visits very often the former vizier of justice, Bouchaib Doukkali. Went several times to Great Britain, but did not go there for more than a year." (actually made only one voyage to London and remained there one year and a half by his brother Mohammed, between 1927 and 1928).

-

Mohammed, "26 years old approximately. Usually resident in London, where he deals with the trade installed in this city by his father. Did not reappear in Salé since more than a year. Passably learned in Arabic. Speaks fluent English and sufficiently French ".

-

Abdelmajid, "22 years old approximately. Attended during a short period the school of the notabilities sons of Salé, but left this establishment to pursue his islamic studies in the city of Naplouse in Palestine. Speaks some French. Disabled, club-footed person."

-

Abdelkrim, "20 years old" and Said "17". "These two are the authors of the letter adressed to ben Abdelkrim in his exile. Attended the school of the notabilities sons of Salé during two months. Have learned only some french words, but do speak fluent english. On their return from London a week ago, they presented a request for the renewal of their passports to join their brother Abdelmajid in Naplouse where they intend to pursue together their studies in the Islamic University."

Questioned on the mobiles of their writing to Abdelkrim Al Khattabi, Abdelkrim would have answered - so the French Controleur Civil - that this letter was written under the influence of the Moslem milieus in the United Kingdom, which were much interested to know the fate reserved to the hero of the Rif revolution, especially since he was condemned to the exile. This declaration was commented as follows:

"Abdelkrim Hajji is a very young man, but he seems to belong to this category of young excited Moroccans who are at the mercy of all the suggestions and see in the eastern earth of Islam the only land which holds the monopoly of Islamic science. He is a potential agitator and deserves that we keep a watchful eye on his activities."

The French controleur added in his information sheet that Abdelkrim had decided to go abroad to get a better instruction as that proposed to him in his own country where his compatriots receive a defective education.

The General Resident seized this opportunity to write to the Minister of Foreign Affairs that he did not consent to the request introduced by the Hajji brothers to allow them go to the Palestinian city of Naplouse, estimating that "it was out of question to accept that the education of our young protégés is done by others against our interests." This decision was communicated to the Directorate-General of the Public education, in reply to a letter addressed on February 24, 1930 to the Directorate-General of the Indigenous Affairs with the conclusions of a report drawn up by Mr. Terrasse, professor at the Institute of the High Moroccan Studies in Rabat as a result of a mission of inquiry in the Middle East. Mr. Terrasse wrote in his report that the University of Naplouse was "famous for its Moslem fanaticism and its xenophobia." Moreover, "One receives there lessons of nationalism and fanaticism which may cause harm to the colonial powers.."

Another information sheet gives a detailed report on the assiduous frequentation of the Hajji brothers to the bookshop of Mohammed Chemao in Salé, where they can read the Egyptian reviews as well as the Syrian, Tunisian and Algerian newspapers which are not prohibited. Two of these publications - Egyptian periodicals - published the relation of voyages in various parts of the world accomplished by the well known journalist Younès Bahri. In one of these publications, the reporter did not fail to judge with an extreme severity the policy of the French Protectorate in Morocco. The second periodical which has just started to publish the impressions of the irakian voyager reproduced a photograph of himself in the midst of a group of Moroccan nationalists, which was taken in the patio of the Merini house in Salé. One recognizes on this photo Abderrahman and Said Hajji "two brothers who were among the first actors to take part in the current agitation. the second of them has distinguished himself by the letter which he wrote to Abdelkrim."

The episode of the protest movement against the Berber dahir of May 16, 1930 having been largely commented on in the part devoted to the Berber question, we limit ourselves here to recall that the idea of the "latif" was the fruit of a personal initiative of Abdelkrim Hajji, who can thus be regarded as the heart of the movement and the principal instigator of the protest demonstrations which started in Salé and gained all the country.

It has been announced that a group of the most virulent leaders composed of Abderrahman Hajji, Abdellatif Sbihi and Mohammed Hassar dispatched an emissary to a meeting held in Rabat in which took part notabilities and representatives of the youth "to tell them that the situation requires that they should shake their torpor and make common cause with their neighbors."

The documents preserved in the archives of Nantes inform us about the visit paid by many visitors of Salé and Rabat to Abdellatif Sbihi's mother to express their whole solidarity with her son who was the first to stigmatize the Berber Dahir and had just been arbitrarily arrested. This one encouraged her visitors to persevere in their resistance and declined the financial assistance which was proposed to her. The two Hajji brothers authors of the letter to Abdelkrim, accused of recidivism after the prominent role they played in the last events in relation to the Berber question, were forbidden leaving the Moroccan territory. They had to wait until mid-october for the authorization to leave for Beyrout, and not for Naplouse as previously requested, to continue their studies in the Islamic University of Lebanon, because their presence in this country would allow the French Autorities to exert a strict monitoring on their extra-curricular activities, Lebanon being at that time under the French mandate. At the beginning of November, they embarked in Tangier for Alexandria via Marseilles, and continued their trip by railway to Lebanon, where their brother Abdelmajid, who had to leave the University of Naplouse for the Islamic University of Beyrout was waiting for them. The General Resident of France in Rabat, Lucien Saint, informed the High commissioner of France in Lebanon of their departure and asked him to have a watchful eye on their activities and keep him informed if they do not respect the engagements which they took before their departure to abstain from any political or journalistic activity.

But the watching measurements did not prevent them from supplying the Eastern press with articles stigmatizing the policy of the French Protectorate in Morocco. They transformed their appartment into a genuine antenna of the Moroccan patriotic movement which started to appear in the principal cities of Morocco, and in particular in Salé.

The Hajji brothers were several times denounced to the police autorities for their regular participation in the collections of funds needed by the national struggle for liberty and justice. Abderrahman, who took an active share in collecting the subscriptions in favour of the Moslems of Jerusalem, was ordered by the French authorities of civil control "to pour the funds collected to a charitable organization or to give back to each subscriber the amount of his subscription."

Abderrahman was also an active member of the support committee which was in charge of collecting funds in favour of the inhabitants of Medine who were threatened by famine. This committee was composed of Abdelkhalek Torrès in Tétouan, Abdelkader Zhiri in Tangiers, Allal El Fassi in Fès, Mohammed Elyazidi in Rabat and Abderrahman Hajji in Salé.

Abdelkrim, who was among the visitors who came to see Abdellatif Sbihi's mother in order to express their solidarity with her son, who had just been arrested, declared on this occasion that he was in possession of an amount of money that he received from three notabilities of Salé, without revealing their identity, and informed the assistance that this money was intended to constitute a lawyer to defend Mohammed Chemao who had been put in goal with the motiv that he addressed an anonymous letter criticising harshly and insulting the cadi of Salé for not ordering the prayer of "Al Istighfar" during the movement of protest against the Berber Dahir.

Concerning the same affair, a note of the police department dated on July 24, 1931 reveals that during his summer holidays in Morocco, Abdelmajid Hajji was indicated by his young comrades to collect subsidies intended for Mohammed Chemao, who was assigned to forced residence in Meheridja.

As for Said, he was entrusted, together with his companion Abou bakr Kadiri, the mission of collecting the funds intended to cover the expenses of the publication of the "Plan of Reforms" and to assemble the annual subsidy due by the Nationalist Movement to the review "Almaghreb" which was published in Paris.

According to an information bulletin of June 19, 1935, a musical evening has been organised in the residence of Mohammed Msattas, the maternal grand father of the Hajji brothers. During this evening, Said Hajji proceeded to a collection of funds intended to cover the expenses of the voyage to Tétouan of the members of the National Action's Committee.

In the same order, a letter of the police department, dated January 20, 1938 announces that Said offered in his domicile a lunch to a group of local nationalists and after the lunch, he opened a subscription to assist the private school of Salé, whose director Abou Bakr Kadiri was detained in prison.

February 11, 1935, a confidential note of the Police department mentions that a meeting has been held the day before in the residence of Ahmed Hajji; and to this meeting took part the main nationalist leaders: Allal El Fassi, Mohammed Elwazzani, Mohammed Elyazidi and a group of ten patriots of Salé "known for their francophobe feelings," among which the brothers Abderrahman and Said Hajji, Mohammed Hassar, Haj Ahmed Maâninou, Mohammed Chemao and Abou Bakr Kadiri. The author of this note specifies that "it would have been lengthily question, during this meeting, which was prolonged late in the night, of a Moroccan delegation at the Society of the Nations in Geneva," and that Mohammed Hajji, tradesman in London, whose frequent passages were signalled recently at the border post of Arbaoua "(separating the french zone from the Spanish one)" would have brought a significant amount of funds that he had assembled between Casablanca and Rabat among the nationalist elements of these two cities.

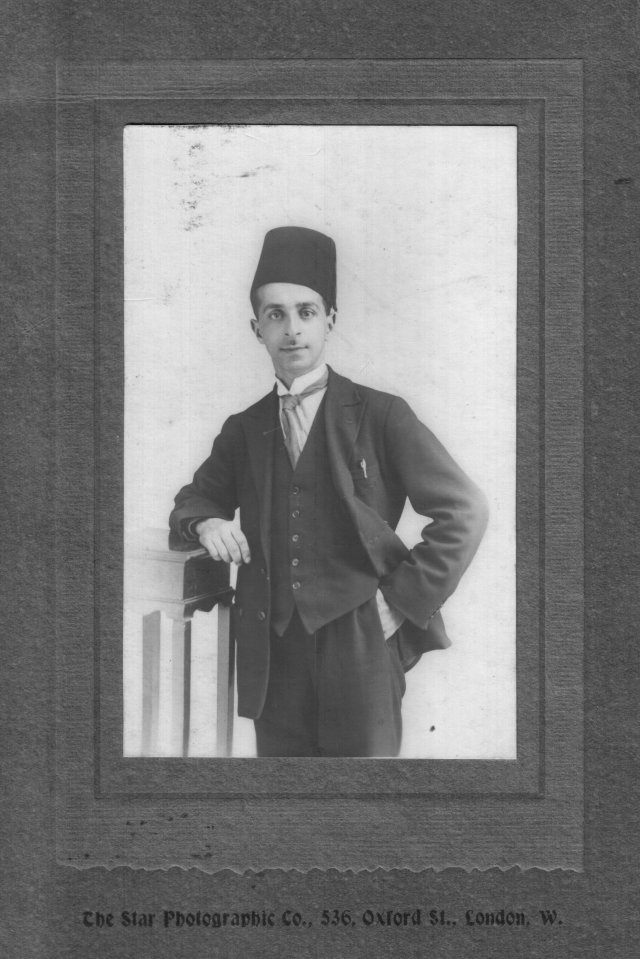

Mohammed Hajji - London 1929

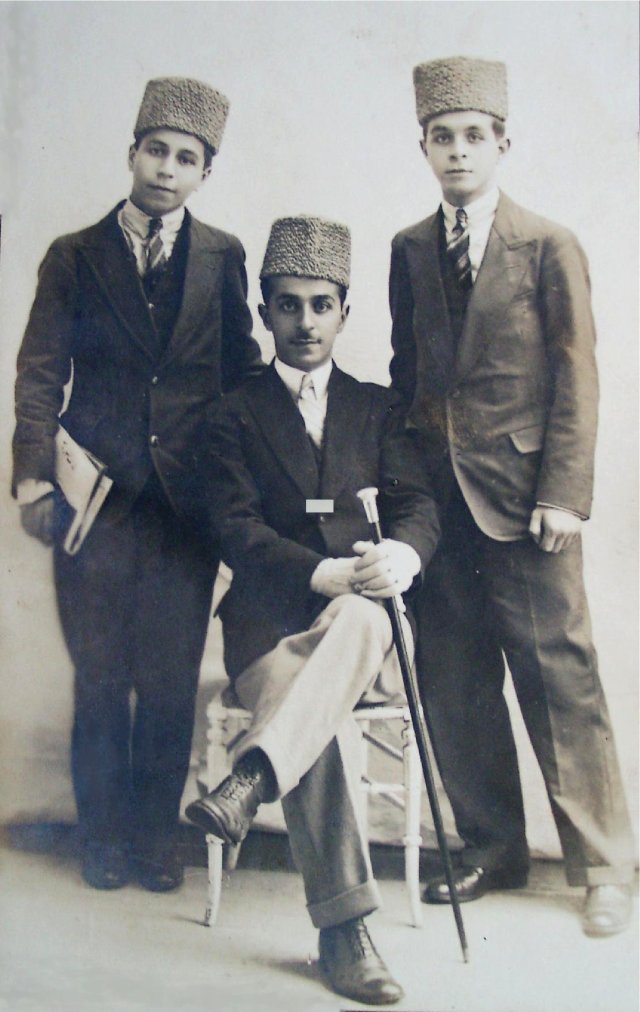

Mohammed Hajji entouré de ses frères Saïd à sa droite et Abdelkrim à sa gauche. Photo prise à Londres en 1929

November 8, 1935, Mohammed Elyazidi and a group of the nationalists of Rabat and Salé paid a visit to Mohammed Hajji, who just came back from London, to listen to his comments on the press coverage of the Moroccan events, and to get informed about the festivities which were organized each year in the United Kingdom to celebrate the feast of the Throne. During this meeting, it has been decided to create a committee which would be charged to collect funds in order to support the struggle of the Abyssinians against the Italian occupation of their country.

As regards the Throne festivities, it is necessary to specify that Mohammed Hassar was actually the first who published an article to propagate the idea of introducing the celebration of the Throneday into the calendar of the islamic feasts.. The intellectual honesty requires that this merit be recognized to him.

But, for the historical exactitude, we cannot ignore that the initiative to create such an national event is to be attributed to Abderrahman Hajji, who proposed the idea for the first time to the group of the young patriots of Salé in one of the meetings held by his brothers in their maternal grand father's house during the summer holidays of 1932. This proposal was germinating in his spirit since 1929,when he returned from his stay in the Unitel Kingdom where he saw how the celebration of the coronation day was important for the institutional monarchy. The meetings of the young patriots continued to be dedicated to this matter until Mohammed Hassar, who was one of them , published in february 1933 his article on "the islamic feasts" in which he suggested that the coronation day must be officially celebrated every year to reinforce the existing ties between the monarchy and the Moroccan people. This article has contributed a great deal to promote the project of institutionalizing the feast of the throne, since all efforts were then mobilized to celebrate this event for the first time at the occasion of the coming 18 november 1933.

As it has been mentioned before, the police department put a watch on the Hajji brothers suspected activities.

Mohammed, in particular, was pointed out to each one of his travels to Morocco which did not cease intriguing the police authorities. A confidential note of February 7, 1934 evaluated these travels which he used to make by air at least once a month with an amount of more than 20.000 francs and estimated that this sum could by no mean be supported by his trade which "was limited to run out of Moroccan objects of modest value" and concluded that "this unusual activity was caused by more political than commercial reasons." The same document added that "this young suspect would receive money from the Ambassador of the German Reich in London!" and came to the conclusion "that it is urgent to inform the Direction of the Indigenous Affairs of these suspect comings and goings, so that a discrete watch will be exerted on his political activities in London, and especially in London."

April 12, 1935, his presence was announced to a dinner offered by the leader Allal El Fassi to the group of the nationalists of Fès.

July 10, a letter addressed to the Director of the Indigenous Affairs reports that "Mohammed Hajji, known as a revolutionary nationalist, was on July 3 in Paris coming from Morocco, and took the same day the train for London, where his brother Abdelmajid was exploiting a trade of leather handicrafts." This letter presumes moreover, that he "would be in charge of a mission by the leaders of the Panislamic Movement in Berlin, and that it was not possible to have further informations on the objectives of this mission."

September 23, he is again reported to be in Fès, in the residence of Allal El Fassi.

October 18, he sent by the English post office a telegram to his father by the means of the British General Consul to Rabat, who came in person to Salé to give the message to his recipient who retained him to dinner.

This information sheet gives a report on the frequent visits of Abdelkrim and Said to the General Consulate of the United Kingdom to Rabat to withdraw English newspapers, pretexting that "the British press provides an account of the exact truth on the state of the hostilities in Ethiopia." The same source adds that "these two nationalists who have the practice of the English language translate to their comrades the articles of these newspapers and accompany their translations by critical comments against the newspapers of Morocco which are submitted to the residential censure."

November 3, 1937, the arrival of Mohammed Hajji at Tangiers is announced to the Directorate of the Political Affairs. Then, it has been brought to the knoweledge of the Police Headquarters that he would have held anti French remarks in a coffee, "saying in particular that, for the Morrocans, it is an honor of going in prison after a revolt."

June 18, 1938, he is announced at his exit of the French zone, in company of Moussa Doukkali, the son of the former Minister for justice. The same note adds that "the visitation operated by the customs authorities as well on his person as in his luggage did not give any result." Mohammed Hajji was often charged to carry out missions on behalf of the National Movement.

Moreover, he never hesitated to assist his brothers, who lived in his appartment in London during one year or more. He helped Said to finance the acquisition of new printing machines and Abdelkrim to settle on his account in America.

Mohammed et Saïd Hajji à la Foire des Industries Britanniques en 1936

Mohammed et Saïd Hajji en visite aux diff\'erents pavillons de la B.I.F. en 1936

Ahmed Hajji et son fils Abdelkrim se dirigeant vers la Foire des Industries Britanniques à Londres en 1937

Abdelkrim Hajji parti s'installer à son compte à New York grâce au soutien matériel et moral de son frère Mohammed - 1937

Another note of information established by the chief of the police department in Rabat, registers the arrival of Abdelmajid Hajji at Salé on october 21, 1935. after a stay of more than a year in England. The same evening a dinner was offered on this occasion, to which the British Vice Consul was invited to take part. The following day, "a large meeting took place in the Msattas house now belonging to the Hajjis, to which assisted almost all the young nationalists of Salé." During this meeting, Abdelmajid welcomed the assistance, and insisted in his speech on the imperious necessity to remain united and respect all the instructions of our leaders in order to achieve the goals we are struggling for. He was extremely pained by the translation of the ashes of Marshal Lyautey, and exhorted the assistance to take the opportunity of the arrival of the journalists invited to cover this event to assist them and give them all the informations they need about the real situation of the country, so that they will see by themselves why we are disappointed and thoroughly dissatisfied with the course of the events.

October 29, 1935, the "Civil Controleur" chief of the district of Salé wrote to the "Civil Controleur" head of the Region of Rabat that "Abdelmajid Hajji went daily to Rabat to meet with Ahmed Balafrej, director of the Guessous Institute."

Said and Abdelkrim, the youngest of the Hajji brothers, were always in a total entente, and were associated since the end of the Twenties and the beginning of the Thirties in all the steps of the political process. We saw that they jointly wrote from London the letter which was addressed to the chief of the Rif Revolution Abdelkrim Al Khattabi in his exile in the Island of "La Réunion". They also signed in common a politico-cultural proclamation which they addressed during their stay in England to the literary Club of Salé, when it obtained the official authorization to exert its activities two years after its creation. They took part together in the movement of protest against the Berber dahir in which Abdelkrim in particular distinguished himself as the genuine soul of the movement. Both Said and Abdelkrim were exposed to a measurement of prohibition to leave the country at a time they were planning to join their brother Abdelmajid in the Middle East to achieve their studies in the University of Naplouse.

They were registered in the same coranic school, received the same particular courses at home, attended the same institute in London to perfect their knoweledge of English, and achieved together their studies at the universities of Beirut, Damascus and Cairo. They led a common campaign of awareness towards the Eastern press as regards the Moroccan question and the harmful consequences of the dahir of May 16, 1930. During their summer holidays, they initiated in Salé a series of meetings with a group of friends who shared the same ideals and nourished the same patriotic fervour which animated them. This group of young intellectuals constituted since 1932 the first cell of the political activities which gave birth to the National Movement. They signed the same petitions and telegrams of protest which were addressed to the Highest Authorities of the country as well as to the General Resident of France in Morocco and the French Government. They counted among the group of pioneers the most engaged in the political struggle and were allowed to belong to the "taifa", which was the most secret cell of the National Movement. They carried out the collections of funds each time the political circumstances required it. One saw them together reading the foreign newspapers in Chemao's bookstore. which was an agent for Morocco of newspapers of the Arab world. One saw them in the British General Consulate to Rabat where they had the possibility to have access to the English newspapers to which they granted more credibility than to the newspapers printed in Morocco under the conditions imposed by the protecting power. This common presence on the political scene continued until 1936, date on which Abdelkrim left for New York where he settled on his account.

Saïd debout à droite d'Abdelkrim - 1928

But the fact that he was absent from home could only confirm him in his patriotic faith. He started far afield to propagate the Moroccan question by supplying the press with articles denouncing the colonial policy exerted by the Government of the French Protectorate in our country.. He addressed these articles as well to the newspapers published by the Arab colony residing in America as to the American press such as the New York Times and other newspapers with a very wide distribution. He also had access to "the voice of America" thanks to his good relations with the head of the Arabic Section of this broadcasting corporation.

A letter of Allal El Fassi dated September 3, 1950 coming from Tangier, informs us that he was aware that Abdelkrim entered into a continuous correspondence with the leading members of the Istiqlal Party, and in particular with Ahmed Balafrej and Mohammed Elyazidi. This letter gives a report on the great interest carried by the leadership of the party with the contacts established with the "Voice of America" and announces the sending of more informations on our national activities to be broadcasted on radio and diffused through the written press nationwide. In this same letter, the leader Allal El Fassi asks him not to hasten to enter to Morocco before receiving new instructions. Abdelkrim continued to take part in the actions of collection of funds decided by the National Action Committee and later by the National Party. He sent regularly to his family clothes to be distributed to the poor. When the leaders of the National Party were sent into exile after the events of 1937, he addressed to the Minister of Foreign Affairs and to the French General Resident in Rabat telegrams denouncing the arbitrary measurements taken against them.

In 1939, Abdelkrim returned to Morocco, his father having called upon him to accompany him in England for the opening ceremonies of the British Industries Fair. When he left London, he did not know that he saw there for the last time his brother Mohammed who died in early 1941 of the following of a serious disease. The news of the death of his brother reached him in New York, and he was obliged to return to Morocco to share the affliction of the family. But when his younger brother Said died one year later, nobody could inform him of such a disaster. Was the fact of not informing him intended to spare him? Or was it because of the difficulties of communication due to the intensification of the hostilities after the entry in war of the United States? Whatever the reason was, he learned the news only incidentally, a long time after the sad event happened, and could neither come back to his country before the end of the war, nor even correspond with his family in Salé, the postal connections being at that time almost inexistent. Fortunately, he knew an American officer who was stationed in Morocco; and it was through him that he could from time to time ensure the transmission of the mail he addressed to his family. At the end of the war, the French Consulate in New York refused to extend his passport under the motiv that his presence was undesirable in Morocco and that he has better remain where he was. But, in spite of this refusal, he took the risk to come to his country with an out-of-date passport and succeeded in crossing the border without drawing the attention of the control Authorities.

Shortly after the death of the founder of "Almaghrib" at the beginning of March 1942, the direction of the daily newspaper was entrusted to Kacem Zhiri who was the nearest collaborator to Said and his right arm in organizing the journalistic activity and in participating with his writings in the editorial board. The new direction was confronted with the difficulties of provisioning and renewal of the print equipment which could not be imported from abroad because of the intensification of the hostilities and especially of the blockade which was then imposed on all the countries of the area. But, in spite of all the material and financial difficulties, "Almaghrib" continued to appear until January 29, 1944, date on which the Istiqlal Party, newly created, published "the Manifest of Independance" arousing the occupier's anger and provoking a bloody confrontation with the occupation's army in Rabat and Salé. "Almaghrib" had to cease appearing on the day which followed the audience granted on January 28, 1944 by His Majesty the Sultan to the emissary of General de Gaulle to the Foreign Affairs, Mr. Massigli, who came to invite him "to respect the agreements of the Treaty of Fès."

"Almaghrib" saw all its activities stopped until April 7, 1952, date on which Abdelkrim Hajji, who decided to come back from the United States, succeeded in reviving the newspaper after an eclipse of eight years, and published the first number of the new series ten years after the passing of its founder. He collected the funds and mobilized new energies which were necessary to the restarting of the press activity.

He renovated the office of printing works Al Oumnia in Rabat, renewed the stocks, initiated vocational training for a new generation of linotypists and called upon new recruits to complete the former editorial team of which many of its members were locked up in gaol as a result of their participation in the events which shook the southern part of Morocco.

Kacem Zhiri, successeur de Saïd en qualité de directeur du journal "Almaghrib" - Photo datée de 1928

Reprise en mains du journal "Almaghrib" par Abdelkrim Hajji en 1952 - Photo datée de 1950

April 10, 1947, the King made a historical speech in Tangier claiming the independence of the country and its territorial integrity. The French Government reacted strongly against this speech, and less than two weeks later, the General Resident of France to Rabat, Erik Labonne, was replaced on May 13, 1947 in his functions by a hardliner, the chief of the general Headquarters of the National Defense, General Alphonse Juin.

The French-Morrocan relationships worsened, and the political climate reached a degree of tension as the country never knew before. The new "Resident General" who came with the idea to play the role of the leader of the colonialist lobby, addressed on January 26, 1951 a warning to the Sultan giving him the choice between repudiating the Party of Istiqlal, or renouncing the privilege of the throne. with the threat of relieving him if he does not execute what he ordered him to do.

In September 1951, General Juin is himself replaced by an other hardliner, General Augustin Guillaume. One month after the installation of the new Resident, he wanted to set up advisory chambers; but the elections which he planned to organize at the end of October were boycotted by the Moroccan people, and a huge demonstration took place in Casablanca.

The reappearance of "Almaghrib "under the directorate of Abdelkrim Hajji took place in April 1952, at a period marked by the resumption of the dialogue between the King and the French Government.

March 14, 1952, the Sovereign asked the French Government to recognize Morocco's right to independence and enjoyment of public and trade-union liberties and exhorted the French part to open negotiations in order to achieve these objectives. The French Government proposed an alternative suggestion with the formula of the "interdépendance" and the creation of common councils and a mixed administration. This counter-proposition was rejected by the King. Then, the events precipitated with the assassination of the Tunisian trade unionist leader Ferhat Hachad, and the solidarity of the Moroccan nationalist milieus with the Tunisian trade-union organization. In these circumstances, Abdelkrim Hajji was arrested and sent into exile to Goulimine, in the saharian part of Morocco, where he was forced to remain for more than two years, to have signed with Abderrahim Bouabid and Mohammed Ghazi a telegram of condolences addressed on behalf of the journalists of the Istiqlal party to the General Union of the Tunisian Workers. It was the darkest period of the history of the French Protectorate in Morocco.

In March 1953, the services of the Residence orchestrated a scene setting of the lowest category by making sign a pseudo proclamation by a score of notable assets to their obedience, accusing the Sultan of leading the country towards chaos and being combined with illegitimate political parties.

August 13, 1953, General Guillaume asks the Sultan, under the threat to remove him from his throne, to give up his attributes of sovereignty and the enjoyment of his political rights.

August 20, the French Government yields under the pressure of the lobby of the colonists who obtained the exile of Mohammed V and the members of the royal family. The adventure ended initially in Corsica, then after a while in Madagascar.

It is not the place to point out here the popular movement of revolt caused by the remoteness of Mohammed V from his throne and his replacement by a marionette who was on several occasions the target of attacks perpetrated against his person. The most essencial thing is that the return of Mohammed V from his exile occured at the same time as the independence of the country, and that the construction of new Morocco was henceforth the top priority. The country knew a euphoric period, during which several operations were launched to catch up on the lost ground. The first of these operations was the Road of Unity whose construction was dictated by the will to seal the reunification of Morocco by connecting the old French and spanish zônes through the chain of the Rif mountains. This mobilization without precedent of the Moroccan youth made it possible to pose the first stone of the construction of independent Morocco. The country proceeded during this very period, with the launching of specific operations, such as the operation of "ploughings," "schools" and an in-depth action of "fight against illiteracy."

Shortly after the independence, "Almaghrib" recovered a new youth, under the responsibility of its director Abdelkrim Hajji, before changing, upon the initiative of Mehdi Ben Barka, into a newspaper with the mission of becoming the main instrument of the fight against illiteracy. It was thus clearly dissociated from the other arabic daily "Al Alam" which was the official newspaper of the Istiqlal party. "Almaghrib" changed its name into "Manar Almaghrib" (the light source of Morocco) and started to appear entirely vocalized to be accessible to the lowest classes for which it was intended. This new edition of the newspaper, unique in its kind, was accompanied by evening courses which were exerted by voluntary young people, who found in "Manar Almaghrib," in the total absence of appropriate books on the market, the only pedagogic instrument to direct the uniform teaching methods all over the country, as well as a document which was to be used by those who attended the evening courses to learn the rudiments from the writing and to familiarize themselves with the reading.

Abdelkrim was a patriot who aspired to a life of dignity in a country liberated from the yoke of colonialism. His objective was to serve his nation by recovering its full freedom and becoming aware of its identity which is rooted in a country with multiple civilized facets.

The phase of the struggle for the independence in which he took part since his early youth enabled him to preach the ideals and the principles of safeguard of our marocanity and our political and cultural identity. To the request of his friend Ahmed Balafrej, who was at the head of the Ministry for Foreign Affairs, he went to New York to renew the contacts he had with the American press and to give a new impulse to the work of public relations he had started there as a private person in order to support the efforts of construction of new Morocco.

His departure to New York coincided with the accession of Morocco to the United Nations which occured on July 20, 1956. This event was followed by the Royal visit of Mohammed V in the United States on November 23, 1957 and the speech he pronounced at the General Assembly on December 9 of the same year.

January 29, 1990, The Istiqlal Party took the opportunity of the festivities commemorating the 46th anniversary of the rising of January 29 1944 in which the populations of Salé and Rabat took part, to associate to this historical event the celebration of an honorary ceremony exciting the services rendered to the nation by Abdelkrim Hajji, patriot of the first hour and one of the principal pioneers of the National Movement.

Said Hajji and his brothers evolved in this family environment where patriotism was transmitted from a generation to another, It is not astonishing that they were aware of their marocanity since their early childhood, and were fully conscious of what their fatherland awaited from each one of them.

Abderraouf Hajji