A native of Salé, Morocco, Said first saw the light of day on February 29, 1912. He was the youngest of a family of six children, with four brothers and one sister. Very early in his childhood Said was aware he belonged to an lineage whose ancestry stretched back to one of the most prestigious men of Salé. His forefather was none other than"Sidi Ahmed Hajji" who had established himself in the city in the late seventeenth century. His tomb, built in the middle of Salé, continues to bear witness to pilgrimages in honor to the patriotic fervor with which he successfully battled the Spanish occupation forces at the port city of Mamora on the Atlantic coast (later renamed Mehdia or "the Gift" after its liberation). His victory led to being ennobled ad vitam aeternam per a Veneration Decree bestowed upon him by the Sultan Moulay Ismael upon receipt of the gate keys of the liberated city.

His father was a merchant who owed his success and fortunes to his commercial endeavors in general and in particular to the successful commerce he maintained with Great Britain. Said thus lived in a milieu of relative ease in an environment where he was avidly encouraged to seek a broad based profession, if only to not be dependent on the government for a living. It was known that the existing administrative apparatus often submerged the individual into an attitude of giving in, reducing him to the unenviable role of a yes man . In particular the fear of being sanctioned, often led the individual to approve without reservation any acts by the government regardless of their nature. He would acquiesce even if the acts were counter to his interests or even if they appear to him to be incompatible with the interests of his country.

Said was aware that staying at arms length from the influence of the governing authority and by relying on the backing of his father who had at his disposal powerful backing by British and industrial world interests, afforded him the opportunity to campaign openly within the ranks of the National Movement. He was thus able to support the Salé chapter of the movement both materially and moralewise without concerns or worries. He derived considerable pride that his father figured among the first petitioners to denounce the misdeeds of the colonial policies, offering his roof as the meeting place for the National Movement leaders.

Said was still a child, aged 7, when his old eldest brother, Abderrahman, aged 18 was named Saad Zaghloul for his patriotic fervor. In particular Abderrahman constantly invoked his readings of Middle Eastern newspapers to which he subscribed, to alert the intellectuals and elite of the third generation of the evolving international events. His elder brother's activism eventually cost him fifteen days of incarceration for stirring support in 1919 against the exile of the former pasha of Salé. The latter was sanctioned for publicly denouncing the new fiscal policies for being seriously biased against small businesses. In a show of solidarity Abderrahman made the rounds of the city inviting everyone to join in a demonstration in support of the exiled former pasha. One wonders whether Said was aware that his eldest brother had written a page in our history by being the first Moroccan to have inaugurated the colonial prisons. The fact remains that events such as this one could not have been lost on a boy of his age who began to see in his older brother a role model for courage and sacrifice for the patriotic cause. This esteem was doubly intensified two years later when his brother championed the cause of Rifian revolution led by Mohammed ben Abdelkrim. Abderrahman went to bat for the revolution by readily offering put his home at the disposal of its leaders to host volunteers and to treat the wounded coming from the battle fields. The defeat of Mohammed ben Abdelkrim in 1926, which was deplored by Abderrahman in a passionate poem declaring his disbelief of such disastrous news. This event marked for Said at age 14, the turning point for a new era., one which would lead him to form with his brother Abdelkrim, two years his senior, and a small group of friends, the kernel of what was later to become Salé's chapter of the National Movement.

Participation in the activities of the Salé Cultural Club

In 1927, Said now 15 years old, helped establish the Salé Cultural Club . He regarded the club as a platform for propagating progressive ideas and for calling upon the intelligentsia to engage in the reformation of attitudes and thinking. He used this forum to urge the elite to distance themselves as much as can be done from obsolete traditions and preserving only those which reflected the vision of a civilized society worthy of belonging to a country with a prestigious history. It was also a forum where he could give free reign to the exposure of his literary and artistic thoughts. He invited his audience to speech and debates on subjects of interest to the young generation. His aims were to revive the luster of the Arabic and Islamic civilization made great by their ancestors through the profit the young elite would derive from spreading its culture and education and through the hopes placed on them to help the Moroccan people to draw strength from the depths of their cultural heritage.

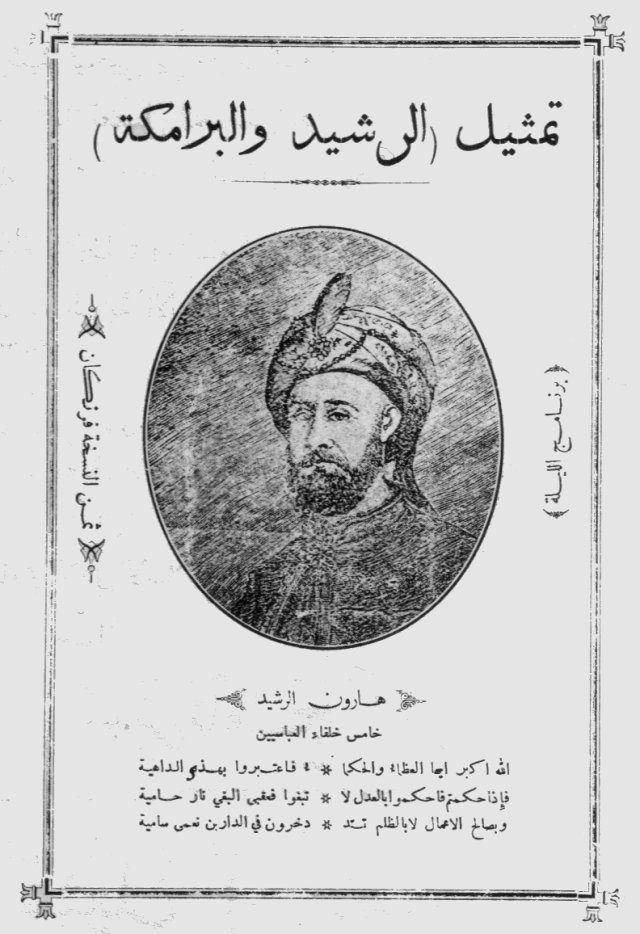

Since its inception in early September 1927, the Salé Cultural Club played an extremely important role in the coordination of local literary and artistic trends. Following the example of other Moroccan towns including Tangiers, Fez, Casablanca and Rabat, the Salé Cultural Club set up a theatrical group composed of the town's young intellectual elite. In the attached photograph showing the acting cast for the play "Haroun Al Rachid and the Baramikas," one sees Said's next elder brother Abdelkrim seated to the right of Abderrahmane Aouad, a writer and future Pasha of Salé. This same set of actors were later cast in the famous play by Francois Coppee, "In the Service of the Crown" a play which had unprecedented success.

La troupe théâtrale de Salé qui a joué la pièce "Haroun Al Rachid et les Baramikes" en 1927 et 1928. On reconnaît assis à la seconde place à partir de la gauche de la photo: Abdelkrim Hajji avec à sa gauche Abderrahman Aouad.

L'affiche de la pièce "Haroun Al Rachid et les Baramikes"

Plans to create a print shop

Very early in his life, Said realized that the propagation of progressive ideas at the national level could not be made possible without the establishment of a commensurate means of communication. He therefore outlined a plan for the creation of a printshop.Without the latter it would have been impossible to solidify the dream he always affectionately had to be the promoter in Morocco of a free press written in his native language.

The founding of the first entirely handwritten newspaper

Starting in 1927, he founded the first private Arabic newspaper that was handwritten in its entirety. He hand copied several dozen duplicates that were routinely destined for distribution to subscribers throughout the main cities of Morocco. This newspaper, titled "Al Widad" which translates to "The Harmony" was the mouthpiece of a society by the same name he founded with a group of his friends. The society's objective was to work for the nation's well-being and to awaken its consciousness. Its motto: "Our motive, our byword, our goal is the racial and religious understanding and harmony between peoples" One could read in one of the editions of this newspaper the words of the famous Egyptian Patriot Saad Zaghloul: "Rights outshine force, the nation out values government."

An account of the theatrical activities of the young elite of Rabat and Salé

Said echoed the theatrical activities made possible by the buoyant elite of the twin cities in a special edition of the "Al Widad" newspaper dated May 7, 1929. This article was written on the opening night of a play cast by the Rabat acting society and he emphasized the cooperation and ties between the youths on both banks of the Boureg-reg river.

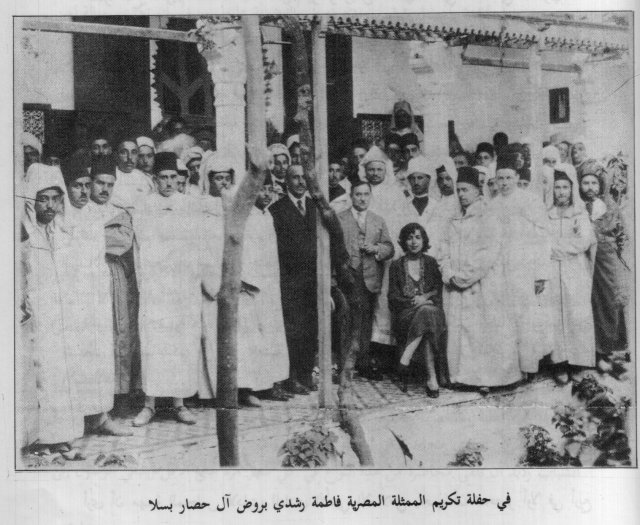

In 1932, at the occasion of a tour in Morocco by an Egyptian theatrical group led by the famous actress, Fatima Rochdi, Said wrote of his impressions of the more than warm reception the Egyptian cast received by the Salé young elite at the grand reception organized in their honor by his eldest brother Abderrahman.

Réception organisée en 1932 par le Club littéraire de Salé au domicile de Mohammed Hassar en l'honneur de la troupe théâtrale égyptienne conduite par la fameuse actrice Fatema Rochdi qu'on voit assise au milieu de la photo avec à sa gauche le frère de Saïd, Mohammed Hajji.

Said's journalistic calling

Said owed his journalistic calling to a precocious leaning for the press as a means of communication and propagation of ideas. He was not satisfied with just the handwritten newspaper "Al Widad" which addressed questions on politics, culture and the arts. The newspaper, which circulated as a 12 page weekly, was augmented with a 24 page monthly titled "Widad" dedicated to literary and scientific studies and research. Next he further enriched the contents of his papers by the publishing a weekly review "The School" that was entirely dedicated to education and educational issues. He followed this effort with "The Nation" where he treated questions relative to the young elite and the cultural arts. Last but not least he collated a photographic catalogue where he displayed pictures associated with current events in politics, the arts and the sciences alongside Moroccan touristic scenery. Indeed his productivity was noted by others including , Robert Rezette , who stated in his book, "Les Partis Politiques Marocains" (The Moroccan Political Parties), that "he (Said) was the most talented literary polemicist Morocco has known."

The role played by the brothers Abdelkrim and Said Hajji in the fight against the Berber Decree

Said spent a year between 1929 and 1930 in the company of his brothers Abdelkrim and Mohamed in London. The sojourn in England distanced Said a bit from his journalistic activities. But that was to change. After returning to Morocco to prepare for their trip to rejoin their brother Abdelmajid in the Middle East, Said and Abdelkrim found themselves in the midst of an extremely grave political crisis, created by what was thereafter referred to as the Berber Question. Both felt it was absolutely imperative to condemn the May 16, 1930 decree which aimed at dividing the Moroccan people into two ethnic groups: a group categorized by their Arabic ethnicity and the other group by its Berber origins. The Arab group would continue to adhere to Islamic law while the Berbers would be submitted to customary law which could vary from one region to the next. The latter group would be excluded from any recourse to jurisdiction under Islamic law. But the absence of a national means of communication rendered the task of denouncing this decree almost impossible. This was especially true since the text of the aforementioned decree, put into question the practice of Islamic teachings which were the country's unifying force for more than a millennium and served in part to inform the community of its obligations. The need for a general mobilization of the Islamic Arab community was never more apparent.

It was under these circumstances that young Abdelkrim had a stroke of genius. He came up with a formula to spread the news by the mobilizing the faithful crowds in the mosques to beg for divine mercy. He called upon the townsfolk to participate without further delay in a protest movement he intended to conduct at the grand mosque of Salé immediately after the Friday prayers. He visited the Imam who was presiding over the prayers to make him aware of the danger befalling the Islamic community. Abdelkrim asked the Imam to publicly denounce the text of the decree and to lead the faithful in the "Latif." This prayer is invoked by Moslems when faced with a major catastrophe in order that they be spared from any calamity threatening their communal well-being.

The desired objective was attained since the series of subsequent events unfolded according to the scenario envisioned by Abdelkrim. Encouraged by his father who told him to not be intimidated by threats from the public authorities, he did not hesitate to claim responsibility for his acts in front of the Controleur Civil. The Controleur, recognizing that he was the principal instigator of the protest movement, had summoned him for interrogation after having submitted his brother Said to a similar treatment. The following Friday, the Latif prayer was invoked not only in the Grand Mosque of Salé but also in all the Koranic medrassas and the neighborhood mosques. To show their displeasure, the authorities arrested the Hajji brothers and three other activists who had participated in the protest movement. The news of these arrests did not take long to spread to the other Moroccan cities and soon after the forbidden prayer was invoked within the walls of nearly all the mosques across the land. Hence Abdelkrim's success in raising the public's awareness and uniting them against the impending danger presented by the Berber Decree, confirmed his rightful place as the soul of the national protest movement. In retrospect, one is permitted, after taking a few steps backwards, to pose the question of what could have been the consequences concerning the Berber question if one had adopted a less uniting scenario than that of the Latif prayer.

Departure of the brothers Abdelkrim and Said Hajji to the Middle East

Said and Abdelkrim were eventually released, but with orders interdicting their leaving the country. This ban was not lifted until the end of November 1930 and soon afterwards they resumed their plans to rejoin their brother Abdelmajid in the Middle East and to pursue their studies. Wherever they stayed during their student years from 1930 to 1935 , be it Beirut, Nablus, Damascus or Cairo, they converted their lodgings into a veritable journalistic information center on Moroccan affairs. They took advantage of their regular correspondence with the leaders of the Salé chapter of the National Movement to relay Moroccan current events. They wrote articles and sent them to the most influential local newspapers and magazines. These included Jerusalem's "Al Arab" magazine, and another Palestinian publication "Al Jamaa Al Islamiya," the Egyptian newspapers "Al Jihad" and "Kawkab Al Charq," the Syrian newspapers "Al Nidaa" and "Al Alam Al Arabi" as well as the Iraqi newspaper "Al Istiqlal." These articles, which were distributed from Damascus then from Cairo were intended to provide the Middle Easterners a better acquaintance with Morocco, to plead for justice and the legitimacy of their cause and to vigorously denounce the colonial policies whose objectives were to divide and conquer.

How the idea of organizing the Moroccan Feast of the Throne was born

The summer vacations allowed the brothers to organize at their residence a series of reunions with other students from Salé. These meetings also gave them the opportunity to resume contacts with the young elites of other Moroccan cities. On one occasion during a reunion held in the summer of 1932, they were rejoined by their eldest brother Abderrahman, who there and then, proposed the initiation of a national holiday to celebrate the anniversary of the enthronement of the King of Morocco. This was a project that he had cherished for a long time. The idea of a Feast of the Throne was revived in an article titled "The Islamic Holidays" that Mohamed Hassar brought to light in the beginning of the year 1933 in a monthly magazine, "Al Maghrib." The idea made its rounds amongst the elite before its initiation. The Feast became an expression of the Moroccan people's will to make it a symbol of their country's sovereignty.

Celebrating the first anniversary of the French language "Al Maghrib" magazine

In the beginning of the summer of 1933, while Said was still located in Damascus, the leaders of the National Movement were preparing to celebrate the first anniversary of the "Al Maghrib." This magazine, which was written in French, was published in Paris under the political leadership of Ahmed Balafrej, under the legal and editorial management of Robert Jean Longuet, with the assistance of a supporting committee of key socialist figures amicable to Morocco's cause. Abdelkrim Hajji was asked by the leading officers of the National Movement if they could organize the forthcoming festivity in his father's residence in Salé. With no hesitation, Abdelkrim responded positively, knowing his father would welcome such an undertaking with enthusiasm. He proceeded to do everything possible ensuring this celebration took place under the best conditions possible in his home on the 8th of July 1933 .

The Official Report on Grievances

Before returning to Morocco during the summer of 1933, Said was made aware of a plan presented to National Movement leaders by Mohamed Hassar who, proposed to develop a grievance report in which all the institutional, political, cultural, economical and social demands to redress grievances would be registered. One goal was to put an end to the fabrications spread by the colonial propaganda that the young Moroccan political leaders lacked maturity and were incapable of properly representing any valid political mission. Said was immediately chosen to be part of a select committee consisting of three participants, namely Said, Ahmed Elyazidi and Omar ben Abdeljalil. Their charter was to meet as long as it took to prepare and document in total secrecy the aforementioned report. The trio met for a period of 40 days at the end of which the report was finalized. The text of this effort was translated later into French with some enhancements to its format and then presented in 1934 as an official document by the National Movement. It was relayed to the highest authorities of the country as well as to the government of the French Republic and to the French Resident General in Rabat. This Official Report on Grievances became a reference document that was invoked each time it was necessary to justify the legitimate aspirations of the Moroccan people for dignity and freedom to choose their own destiny. In 1937 it was presented anew in summary format limited to the most urgent of demands by the "Assembly for National Action" a.k.a. "Al Koutla Al Watania" which succeeded the National Movement .

Induction of the brothers Abdelkrim and Said into the "Taifa" Cell

In 1934, again during the summer vacations, Said and Abdelkrim were amongst the first to be inducted as members of a secret cell known as "Taifa" whose mission was to steer the National Movement, and then later the patriotic Party. The members were bound by an oath before Allah and the nation to protect under the seal of secrecy all the decisions taken in its bosom. Made up of about sixty members, of which a dozen from the Salé chapter, Taifa counted in its ranks the key leaders of the National Assembly as well as a certain number of young activist patriots. The membership included such national heroes as Abderrahim Bouabid, Mehdi Benbarka, Kacem Zhiri, Abdallah Ibrahim, Abdelkebir El Fassi, Tahar Zniber, Seddik Ben Larbi to name just a few. Membership in the Taifa was highly selective and was not granted without the candidate having already rendered some invaluable service to his nation and to the political entity to which he belonged.

Rejection of the petition for authorization to publish a cultural magazine

Upon his definitive return to Morocco from the Middle East, Said eagerly sent to the Grand Vizier, care of the Bureau for Indigenous Affairs in Rabat, a letter dated June 1935. The letter solicited the authorization to publish a cultural magazine to be named "Marrakech." The authorization was denied without due cause. Said immediately contacted the French Resident General in Rabat in protest. He alerted Resident General of his regrets that the act of rejection of an authorization for the purpose of allowing the publication of a magazine whose contents were to be strictly cultural, would by its nature lead to serious damage to the image and honor of France, a country reputed to be the nation of Human Rights and Civil Liberties.

Nomination to a follow up committee charged with pursuing demands for the freedom of the press

Faced with the persistence of the protectorate authorities in refusing authorization for any publishing of newspapers in Arabic, the Assembly for National Action, decided to confer to a special committee the task of pursuing demands related to the freedom of the press. Consisting of three members, Mohamed Elyazidi, Brahim El Kettani and Said Hajji, this committee began its work by proceeding to distribute a pamphlet on September 17, 1936 that gave a detailed account of the rejections of the numerous requests made to the colonial administration in order to obtain the necessary authorizations. The pamphlet showed the requests had been denied regardless of newspaper's direction be it of a political, informative, literary or cultural nature. This same pamphlet also informed the public of the establishment of a follow up committee made up of persons whose requests for authorization to publish were not approved and who were therefore committed to use all legal means at their disposal to continue the struggle to "open the doors of the press" in this country. Said took upon himself the task of conceiving plans for this effort in a document divided into three parts:

-

How to open the doors to a free press

-

The categories of newspapers which needed study and practical modalities for production

-

The policies to be followed by the newspapers

Final touches to a text defining the nature of Franco-Moroccan relations under France's Popular Front

The rise to power of the Popular Front in France provided an opportunity for Said to define in a working document the nature of the relations which should henceforth be established between the two countries. He impressed upon the Assembly for National Action the need to emphasize a clear and precise direction. He wanted the body to take into account the real needs of Moroccans in order to best exploit the opportunities presented to them by the new French political realities offered by the new governing party. He proposed the adoption of a five year plan, which in order to be symbiotic with the direction of the Popular Front, would be matched with a political program based on dialogue and cooperation. The plan would be reviewed annually to define the steps to be undertaken and the project objectives for that year..

Memorandum addressed to France's Popular Front

The author (Said) of this document had, incidentally, participated in drafting and editing of a memorandum which the Assembly for National Action had addressed to France's Popular Front government on August 3, 1936. It criticized the "Commission Permanente de Defense Economique" (a standing commission for economic counseling) which, ever since its creation, had done little else but serve the interests of the French settlers. The memorandum stated that the commission worked to the detriment and abandonment of the true natives of this country. It denounced the lack of freedom of the press, freedom of assembly and the right to free trade unions . It also highlighted the commission's disgraceful insensitivity for having erected almost insurmountable barriers which all Moroccans encountered when applying for an authorization to produce a newspaper written in Arabic. In addition it deplored the fact that, even if the authorization is granted, it could be revoked at anytime without the revocation being submitted to any judicial review. Even worse, the Moroccan press written in Arabic came under the legal purview of the military tribunals. The journalist was just as liable facing this type of jurisdiction as a criminal. He would be answerable for his writings in the same manner that a bad actor with respect to common law was to answer for his criminal acts.

Nomination of Henri Ponceau as the French Resident General in Rabat

The nomination of Henri Ponceau as the French Resident General in Rabat was welcomed with interest by the Assembly for National Action. They saw in him an open-minded man capable of standing up to the Conseil Consultatif (Consultation Council). The latter was dominated by highly insensitive members of the French settlers. Its dissolution was called for by all the leaders of the Assembly across Morocco. It should be mentioned that Abdelkrim appears amongst the signatories of the petition presented by the Salé members of the Assembly for the dissolution of this council.

The replacement of Henri Ponceau by the former French Resident General in Tunis.

However the hopes placed on Henri Ponceau were quickly dissipated when he was replaced by the former French Resident General in Tunis who was well known for his extremely rude policies directed against the Tunisian leaders of the "Destour" party (Constitution Party). The replacement of Henri Ponceau by a Resident General less inclined to dialogue sparked a large protest movement across Morocco. The protests were spurred by the example set by the Salé Assembly members who expressed their dissatisfaction via telegrams sent to his Majesty the King as well as the President of the Council of the French Government. These telegrams were signed by Said Hajji, Abou Bakr Zniber, Abou Bakr Kadiri, Ahmed Maâninou, Mohamed Hassar, Mohamed Aouad and Mohamed Chmaou.

The first Conference of the Assembly for National Action

On October 25, 1936, the Assembly for National Action held meetings as part of its first conference in Rabat, with the participation of about a hundred delegates representing the different regions of Morocco. The delegates were called upon to approve the assembly's direction as presented by Allal El Fassi as well as its general policies as presented by Ahmed Elyazidi. They later took part in a general debate to finalize the official report for the redress of the most urgent demands destined to be once again submitted to the authorities in power.

The organizing of demonstrations in Salé and in Fez in support of the recommendations from the Conference.

Meetings to support the recommendations of the conference were organized on the first of November 1936 in Fez and nine days later in Salé. Said Hajji participated in both of these cities where he was invited to speak on the fundamental foundations of civil liberties after opening remarks by Allal El Fassi.

Banning of the planned demonstration in Casablanca and the arrest of the key leaders of the Assembly

When Casablanca was to have its turn for planned demonstrations on November 17, 1936, the participants were surprised to find the protest site invaded by local authorities with the pasha of Casablanca at their head. Upon seeing the leaders of the movement approaching, the pasha went to their encounter to inform them of the ban on the demonstration they intended to organize. The crowd reacted by shouting "Long live liberty!" and by chanting patriotic songs. The leader Allal El Fassi was raised upon the shoulders of the crowd and gave an improvised speech, denouncing the indecent assault against civil liberties but asked the bystanders to disperse peacefully. Nonetheless a few moments later three of the principle leaders, Allal El Fassi, Mohamed ben Hassan Wazzani and Mohamed Elyazidi were arrested.

Solidarity demonstrations across the Moroccan cities to protest the arrests of Assembly leaders

The news of the arrests spread like lightning throughout the cities of Fez, Rabat, Salé, Taza and Oujda where massive demonstrations were immediately organized. In Salé, the procession was set in motion from the home of Mohamed Bekkali in the Bab Hsain quarters and headed towards the mosque housing the Mausoleum of Sidi Ahmed Hajji. Sticking to his principles, Said gave a speech in front of the crowd of demonstrators explaining the reasons for having this protest march. He reminded the crowd that the purpose of the protest was to show the Salé people's solidarity with the Assembly party leaders arrested in Casablanca and to demand their immediate release. He also insisted that the demonstration be held peacefully. After his speech, the crowd marched towards the mosque. Once there, more speeches were made, increasing the resonance of patriotic fervor for the thousands of participants who responded to the call to action for mass protests. The demonstrators were cleared away following new arrests affecting amongst others, Abou Bakr Kadiri, Haj Ahmed Maaninou, Mohamed Bekkali, as well as Said's cousins, Mohamed Hajji and Abdallah Hajji.

Appointment of General Nogues as the new French Resident General in Rabat

The appointment of General Nogues as the new French Resident General in Rabat was greeted like a lessor evil by the Assembly for National Action. Taking into consideration somewhat favorably his previous role as a disciple of Lyautey , the Assembly decided to open with him a period of cooperation, if only to not prejudge the newly formed French Popular Front government which preceded his appointment. However party leaders were forced to immediately change their tone, when Abou Bakr Kadiri was arrested and jailed for having refused to comply to an implicit order that he desist from opening an annex to the "Al Nahda" school. Moreover, the spirit of cooperation was further stifled after Said Hajji and a small band of Salé patriots were in turn arrested and locked up in the same dungeons for several days. Their offense was to have applauded the issuance of a verdict in favor of the detained Abou Bakr who was released. His verdict concluded that his period of imprisonment more than covered the punishment incurred.

The circulation of national newspapers in Arabic , including "Al Maghrib" founded by Said Hajji

But despite everything else, the policy of dialogue bore fruit since from the start of 1937, a number of national newspapers were allowed to circulate including the "Al Atlas" newspaper led by Mohamed Alyazidi, "Amal Al Chaab" by Mohamed ben Hassan Wazzani and the "Al Maghrib" founded by Said.

Banning of the Assembly for National Action

Unfortunately, this ray of light lasted only a brief period. General Nogues , who until then had given the impression he was in support of the policy of cooperation, began to steer a new course in line with the objectives of the settlers. Upon his return from a trip to Paris where he was summoned for consultations, he went to Fez on March 18, 1937 where he brought together the Ulemas and the city's notables, the members of the Municipal Council, the Chamber of Commerce, the representatives of the patriotic movement as well as the French Provincial Governor. He informed the attendees that effective immediately measures were to be taken to ban the Assembly for National Action because of its stated hostilities to the French administrative policies in Morocco.

Creation of the National Party

In April 1937, a new political entity was created replacing the banned Assembly for National Action. "The National Party" was established to fulfill the national demands. The "Al Maghrib" newspaper which had just launched its first issue on April 6, 1937 was first to publish the new party's communiqué announcing its creation. All the Arabic newspapers which recently obtained their authorizations to circulate were unanimous in highlighting some of the coercive actions inflicted upon the Moroccan citizenry. They condemned the expropriation policies on behalf of the French settlers as well as the financial burdens that were placed upon a population reduced to a state of misery without precedent. In the face of this catastrophic situation, the National Party decided to resort to more effective means of resistance and convened a special conference on October 13 , 1937 in Rabat. The conference was set up by the various party representatives from the main cities of Morocco. The Salé branch organized a local meeting on September 29 during which Said Hajji, after Abou Bakr Kadiri's opening speech, gave a presentation with the theme: "Freedom is taken, not given."

The first caucus of the National Party

The caucus was held on the selected date under the chairmanship of the leader Allal El Fassi who proceeded in his opening remarks to analyze the general state of the union and to outline the political objectives assigned to the National Party. Then, speaking on behalf of the Salé chapter, Said Hajji did not hide his pride by noting the heroism of the Moroccan people who struggled to defend their freedoms. He added that "those sacrifices to which we will agree upon today are the price we must bear to realize our legitimate demands." Other orators followed at the podium, including Omar ben Abdeljalil who condemned coercive actions with respect to the Moroccan lands and stated they had no legal bearing. Abou Bakr Kadiri gave a lecture on a proposal for a "National Pact" submitted for approval by the caucus. Structured around eight articles, this pact proposed most notably in article seven that the conference members will cease all dialogue with the government until it renounces its policies of abuse of power, the stifling of freedoms and it agrees to execute on the key reforms submitted for its consideration.

The banning of the "Al Atlas" Newspaper

It should be noted that the day following the special caucus held in Rabat, the "Al Atlas" newspaper (which had received authorization to circulate on February 12, 1935) was hit with a ban effective on October 14 of the same year. Consequently the "Al Maghrib" newspaper became the only national press organ able to provide a voice for the National Party and to relay accounts of its patriotic activities.

Arrests of the key leaders of the National Party following the presentation of the National Pact to French Resident General in Rabat

The National Pact was delivered in Mid-October to the French Resident General in Rabat. Ten days later he responded with a decision to arrest Allal El Fassi and send him into exile in Gabon. Mohamed Elyazidi, Omar Ben Abdeljalil and Ahmed Mekouar were also exiled in different remote locations in the Moroccan Sahara.

The news of these arrests provoked an outcry across the nation. In Salé, a massive crowd converged on the Grand Mosque on October 29 to demonstrate their solidarity with the arrested leaders. Said Hajji participated with the demonstrators, but this time he did not speak as was his typical inclination. Instead he left it to Abou Bakr Kadiri to address the loyal crowd on the purpose of the demonstration before approaching the problems of lack of civil liberties, freedom of association, and the right to assemble, the freedom of the press and freedom to unionize. Here, as in Casablanca, the demonstrators were halted by a number of arrests including that of the speaker who was later to be sentenced to a full year in prison.

Said's political isolation after the arrests within the ranks of the Party

After this wave of arrests, Said found himself totally isolated on the political scene. Even Abdelkrim, who was the only brother to have participated with him in political activities within the National Movement and later the Assembly for National Action, had left Morocco in 1936 for the United Sates of America. Abdelkrim established himself in New York, following the example of his elder brother Mohamed, who managed for several years a business in London. It is true that his commercial undertakings overseas did not prevent him from closely following the political developments in his country. Not only did he regularly send telegrams to the French Resident General in Rabat to denounce the arbitrary character of the arrests or the repeated attempts against the freedom of the press in particular and against the civil rights in general, but he also often took the initiative to draft articles on the Moroccan situation that he sent to the American newspapers in search of gaining their sympathy for the Moroccan cause.

The strategy adopted by Said to breakthrough the impasse.

Said took advantage of the isolation in which he found himself to finalize a strategy allowing him to pursue a number of efforts whose consequences which would allow the country to escape from the political void in which it was placed by the latest events. He knew he was bound by the National Pact which prohibited all dialogue with the protectorate authorities as long as the protectorate power did not renounce its colonialist policies based on coercion and suffocation of basic freedoms and as long as it did not provide any initiation of activities to redress the demands contained in the grievance report. Said determined that it was necessary at all costs to find a solution out of this impasse quickly .The Protectorate Administration would continue to have the upper hand by leaving matters status quo. It had no interest in increasing the stature of the political detainees by any favorable actions and it was not disposed to make concessions with regards to civil liberties or even more generally with regards to the demands formulated in the grievance report submitted for its consideration. Moreover, the "Bureau of Indigenous Affairs" had launched an intense effort with active participation of the "Renseignement Généraux" (General Intelligence) and some unscrupulous native collaborators to undermine the leaders of the National Party. Their plan was to scuttle the agenda of the National Party by hurting its morale and by causing physical harm to the well-being of its leaders.

It was in this environment that Said's political flair came to the fore, even though his acts were later not fully understood or appreciated by a number of fellow militants who expressed their apprehension by reproaching him for taking action outside the rules of engagement set by the National Pact. In actuality, Said had noticed a deep divergence of opinion had loomed between the Resident General and the Bureau of Indigenous Affairs. Sensing that the former had a willingness to be more open, Said judged that one of the essential conditions posed by the National Pact was therefore fulfilled. He felt that, as a member of the moderate wing of the party, it was necessary for him to engage the Resident General directly to cement a relationship that would ultimately result in satisfying his objectives including elevation of the stature of the political detainees and to the implementation of the Reform Plan. To avoid any opportunity by the Bureau to sabotage the emerging negotiations between the two parties, Said took care to ensure no whiff of the meetings reached its members.

At the conclusion of the meetings where everything said by each side was documented in the meeting minutes and signed by both parties, Said made the final adoption of the agreements reached with his French interlocutors contingent on the approval by Ahmed Balafrej. He insisted that he be allowed to see Ahmed at his residence in Geneva to submit to him the accord which once approved, would allow a new era of fruitful cooperation between the two countries. Said traveled all the way to Geneva only to find Ahmed Balafrej in the process of having a surgical operation. Chakib Arsalane, a very close friend, was waiting in a room near the operating room and so Said had a lengthy conversation with Chakib winning him over to the cause. After Said left for his return trip to Morocco Arsalane would wait until Balafrej had completely recovered to make him aware of the discussions he had with Said. It was then that Balafrej confirmed in writing to Said his approval in principal for the agreements as they had been reported to him by Chakib Arsalane.

Based on these facts, how could there be any doubt with respect to the good intentions of a patriot such as Said, who, as we have seen, had in no way acted differently from that outlined by the National Pact. He had, contrary to some misinformation spread by his detractors, done all he could to obtain the release of his freedom fighting companions as well as to ensure that a portion of the grievances were going to be implemented. How could there by doubts of his good intentions given that Said had made all he had agreed to with the Resident General contingent on the preliminary approval by Ahmed Balafrej? The elements of this assessment should be sufficient to remove any misgivings and to lift any ambiguities concerning the loyalty of a man committed to the National Party. We believe that the initiatives taken by Said contributed to the elevation in stature and eventual release of the political detainees and he had at least extracted a promise for a thorough review of the grievance report in order to retain, to the first order, the most pressing of key grievances and to give them a chance to be redressed. These positive developments could only have been taken by a leader with his stature, at a time where almost all the other leaders were either in exile or in prison for an undetermined period. Was this not also, a key moment in the political journey of a man of action such as Said Hajji?

Unfortunately, the second world war broke out at a time when he was fully at the peak of his tactical skills and abilities to drive conversations with the protectorate authorities along lines favorable to the patriotic theses backed by the National Party. He died March 2, 1942 barely reaching age thirty.